Friend’s dealings with advertisers

By Paul Oliver

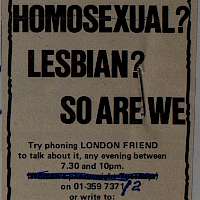

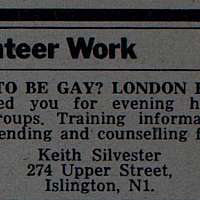

On the whole London Friend didn’t experience too much difficulty placing adverts in the press. National papers such as the Guardian, Observer, Sun and Sunday People, local newspapers such as the Islington Gazette and magazines such as Time Out and Spare Rib were happy to accept them. New Statesman even wrote to Friend to solicit its business: it sent Friend cut-outs of adverts it had carried for other gay organisations and a Friend advert from another publication, pointing out that had Friend been advertising in New Statesman at the time that these adverts appeared, it would have reached 241,000 UK readers. 1

Generally speaking, such (usually short) delays as did occur in the process of placing adverts were due to the need to establish and confirm rates and methods of payment. Sometimes a paper wanted clarification on a particular point and was happy to proceed once this had been received. In April 1977, for example, the classified advertising manager at the Sunday Times wrote to Roland Jeffery, general secretary of Friend, asking him to provide evidence that Friend was supported by the Home Office and Islington Council and also stipulating that the proposed advert should contain a reference to the fact that Friend was a counselling organisation. 2 The necessary assurance must have been given and the copy amended as requested since the next letter from the Sunday Times confirmed that the paper was happy to proceed. 3

Sometimes, though, the process was rather protracted and the request to advertise was granted only after a period of lobbying on the part of Friend to overturn a negative response. Thus, in August 1976 Mirror Group Newspapers, after asking, the previous month, for clarification as to ‘what type of organisation’ Friend was and requesting to see any literature which explained its services, as well as the text of the advert it wished to place in the Daily Mirror, turned down its request on the grounds that Friend’s ‘announcement’ did not fall into ‘a category […] published in the advertisement columns of Mirror Group Newspapers.’ 4 The category, however, was not specified.

Friend’s request for clarification on this point elicited a response from a more senior member of staff at the Mirror supporting his colleague’s decision and stressing that there were ‘no grounds’ for negotiation. 5 But an appeal was made to a yet more senior member of staff and proved successful: as a result of the matter being referred to the editorial director of Mirror Group, it was decided that the advert could be published—provided it made clear that what Friend offered was ‘help and advice’. Since the letter containing the appeal does not appear to be extant, it isn’t clear what fresh tactics Roland Jeffery had employed. However, the letter giving news of Mirror Group’s change of heart was copied to Nettie Pollard, Gay Rights organiser at the National Council for Civil Liberties, so it seems reasonable to infer that recourse was had to her advocacy. 6 (At around this time Roland Jeffery involved her in a similar, although unsuccessful, attempt to reverse a refusal on the part of the Radio Times to carry Friend’s advertising.) 7 The letter from Mirror Group also specified the text of the advert which it was proposing.

At roughly the same time that he was battling with Mirror Group, Roland Jeffery also had to contend with an initial refusal from the Hackney Gazette’s advertising manager on the grounds that his newspaper did not accept ‘this type of copy,’ once again without spelling out which category of copy the writer saw the proposed advert as falling into. 8 Although there is no extant letter which proves that the advert was eventually accepted, the tenor of the surviving correspondence makes acceptance the likely outcome. 9

The three months that it took to get a satisfactory resolution from Mirror Group and the Hackney Gazette are somewhat put in the shade by the eleven months that it took to get an advert placed in the London Weekly Advertiser. This time Friend’s adverts were initially turned down on the grounds that they ’did not conform to [the paper’s] policy’. 10 When this unexplained decision was challenged over the phone, two of the paper’s employees insisted that the paper was not anti-gay. When challenged further, the best that the first of these could come up with was that the paper was ‘a little old-fashioned’. (The second was merely obstructive.) 11 A solution was nevertheless found in the end. Once again it involved agreeing on an acceptable form of words. 12

Occasionally, however, Friend’s request to advertise was met with a refusal which was worded in a way that ruled out any appeal, as was the case with the Sunday Express (estimated circulation 3.5 million), whose editor was the legendary John Junor. In his reply to Roland Jeffery’s request for an explanation of the ‘personal’ decision’ that had been taken not to carry a Friend advert, Junor could barely conceal his distaste at the idea of advertising Friend’s services—this despite Roland pointing out (a) that other national newspapers and magazines were happy to advertise Friend’s services and (b) that Friend offered a counselling and befriending service for ‘distressed and isolated people’ that was funded by both the Home Office and the London Borough of Islington. 13 It was, as I intimated earlier, a similar story with the Radio Times.

Although one would have expected to find a variety of attitudes in evidence in replies to approaches to a range of publications in the period under examination, it’s nevertheless instructive to observe the strength of the sometimes scarcely veiled homophobia underlying some of the negative ones. The patience and persistence with which Roland Jeffery and Richard McCance (who took over from Roland Jeffery in the autumn of 1977) pleaded Friend’s cause is truly remarkable.

Footnotes

- London School of Economics, HCA/Friend/3/1, letter from Robin Cooper to London Friend, 26 October 1976

- Ibid., letter from Derek Mercer to Roland Jeffery, 28 April 1977

- Ibid., letter from Derek Mercer to Roland Jeffery, 11 May 1977

- Ibid., letter from Bobby Sylvestre to Roland Jeffery, 27 July 1976; letter from P. Bailey to Roland Jeffery, 24 August 1976. For the letter from Friend containing the proposed copy etc., see ibid., letter from Roland Jeffery to Daily Mirror, 6 August 1976.

- Ibid., letter from Roland Jeffery to P. Bailey 6 September 1976, letter from Donald Chappell to Roland Jeffery, 8 September 1976

- Ibid., letter from Derek Rogers to Roland Jeffery, 18 October 1976

- Ibid., letter from R. A. Bliss to Roland Jeffery, 27 July 1976; letter from Roland Jeffery to R. A. Bliss, 14 October 1976; letter from R. A. Bliss to Roland Jeffery, 8 November 1976

- Ibid., letter from L. S. Leggett to London Friend, 27 September 1977

- Ibid., letter from D. G. Messer to Richard McCance, 22 November 1977; letter from Richard McCance to L. S. Leggett, 24 November 1977

- Ibid., letter from Janice Wilson to London Friend, 19 April 1977

- Ibid., memorandum of two telephone calls between Roland Jeffery and London Weekly Advertiser (memorandum dated 22 April 1977)

- Ibid., letter from Roland Jeffery to Lindsay Masters, 11 May 1977; letter from Roland Jeffery to Editor, LWA, 11 May 1977; letter from Tessa Reddish to Colin Martin, 16 May 1977; letter from Colin Martin to Roland Jeffery, 19 May 1977; letter from Ron Drain to Roland Jeffery, 19 May 1977; letter from Simon Tindall to Roland Jeffery, 23 May 1977; letter from Roland Jeffery to Ron Drain, 24 May 1977; letter from Roland Jeffery to Colin Martin, 24 May 1977; letter from Roland Jeffery to Simon Tindall, 3 June 1977; letter from Roland Jeffery to Ron Drain, 1 August 1977; letter from Richard McCance to Paulette Doffman, 24 November 1977; letter from Richard McCance to Paulette Doffman,14 December 1977; letter from Richard McCance to Paulette Doffman, 8 March 1978

- Ibid., letter from John Junor to Roland Jeffery, 20 November 1976; letter from Roland Jeffery to John Junor, 17 November 1976