Timeline

In 1971 the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) saw a need for an advice and counselling service which would support and befriend gay people who had problems that could not be solved by CHE, which was first and foremost a campaigning organisation.

120 people attended CHE's first pan-London meeting on 2nd April 1971. At this meeting a working party called Task Force was set up, later renamed the Fellowship for the Relief of the Isolated and Emotionally in Need and Distress (FRIEND) in October 1971. The acronym was swiftly forgotten. FRIEND was the idea of Michael Launder, a social worker and member of CHE.

Not long after, Friend found its first premises at 'The Centre', a community counselling project in Marylebone run by Reverend Peter Royston-Ball. Now they had a place to work from, they began to work out the details of what they would do.

Michael Launder (a social worker who founded Friend) wanted it to be a service run by lesbians and gay men who had been trained to be volunteer befrienders. The befrienders would aim to equip the ‘clients’ with the social skills and confidence to forge a gay or lesbian life for themselves or refer them on to other services better equipped to deal with their needs. Befrienders were not supposed to act as counsellors.

At an early FRIEND meeting at Kingsway Hall in October 1971, there was a debate between Michael Launder, and some of the other volunteers. Launder wanted to professionalise Friend's work, while some of the volunteers resisted this, wanting it to remain a grassroots organisation. Launder argued that that clear boundaries between volunteers and clients were needed to avoid sexual exploitation of more vulnerable and young people, as well as to provide the befriender with a buffer from the emotional demands of the clients. The meeting agreed that volunteers should be given training, but the debate about how professional Friend should be, and who had the right to vet and recruit volunteers, continued into 1972.

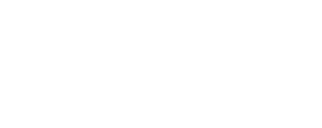

In 1972 Friend was no longer just an idea, it was now hard at work. In May Friend was operating a telephone line, staffed by volunteers and open for calls from Monday to Friday, 7:30 - 9:30pm.

By November 1972, there were fifty befrienders nation-wide, supported by twelve professional therapists. The London operation at the Centre was open seven nights a week, plus there were Friend branches in Manchester, Liverpool, and Cambridge, with ones in Cardiff and Leeds about to open.

London Friend had been the first of the Friend groups, now it was one of many branches, joined together to form National Friend.

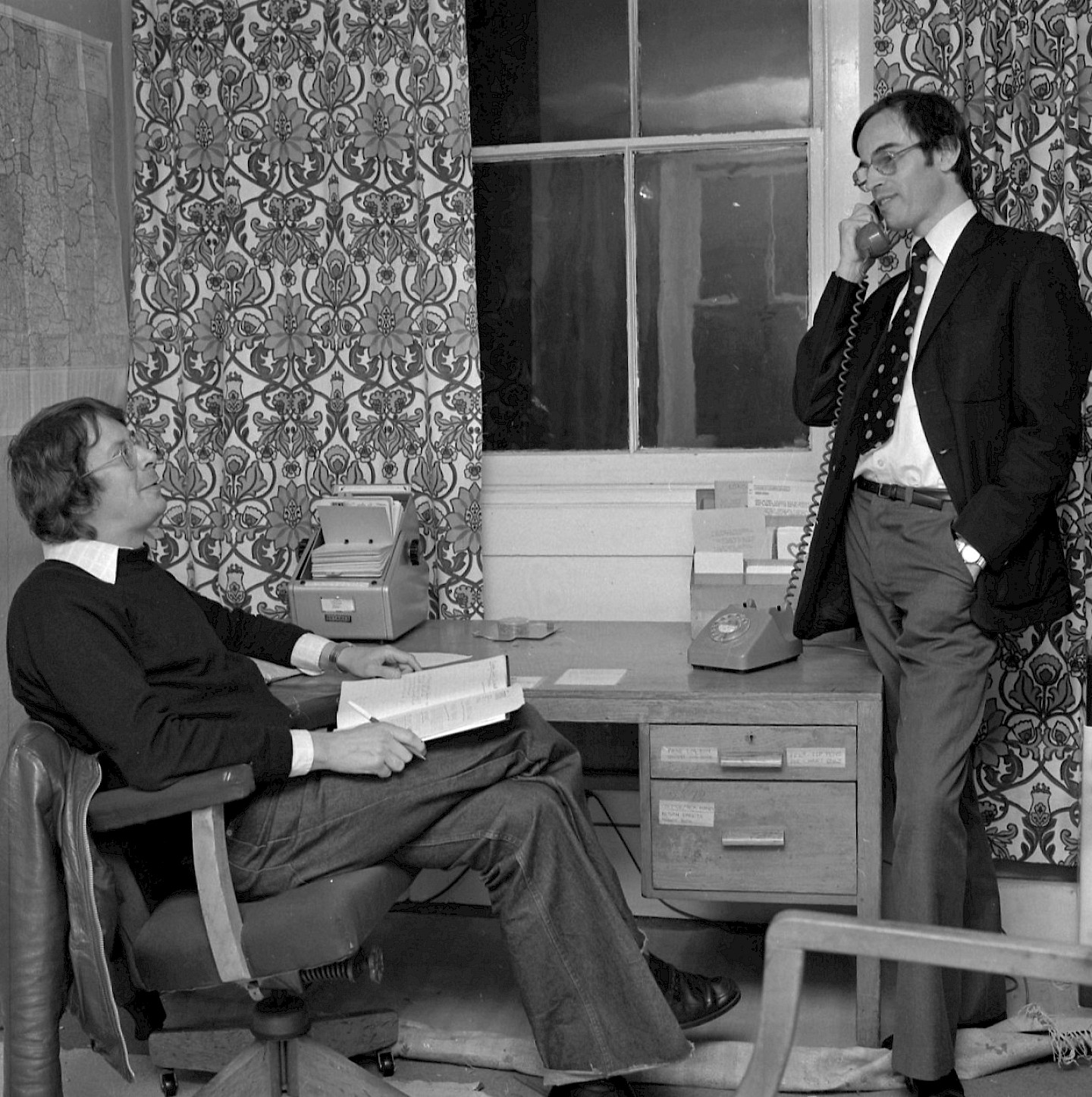

London Friend was awarded an Urban Aid grant in February 1975. This is thought to be the first government grant ever to be awarded to a gay-led organisation and was considered so controversial that the Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, personally steered the grant through. The announcement made the front page of Gay News.

The grant was jointly awarded by the Home Office and Islington Council. It was stipulated that London Friend would receive nearly £40,000, to be paid at a rate of £7,900 per year for five years.

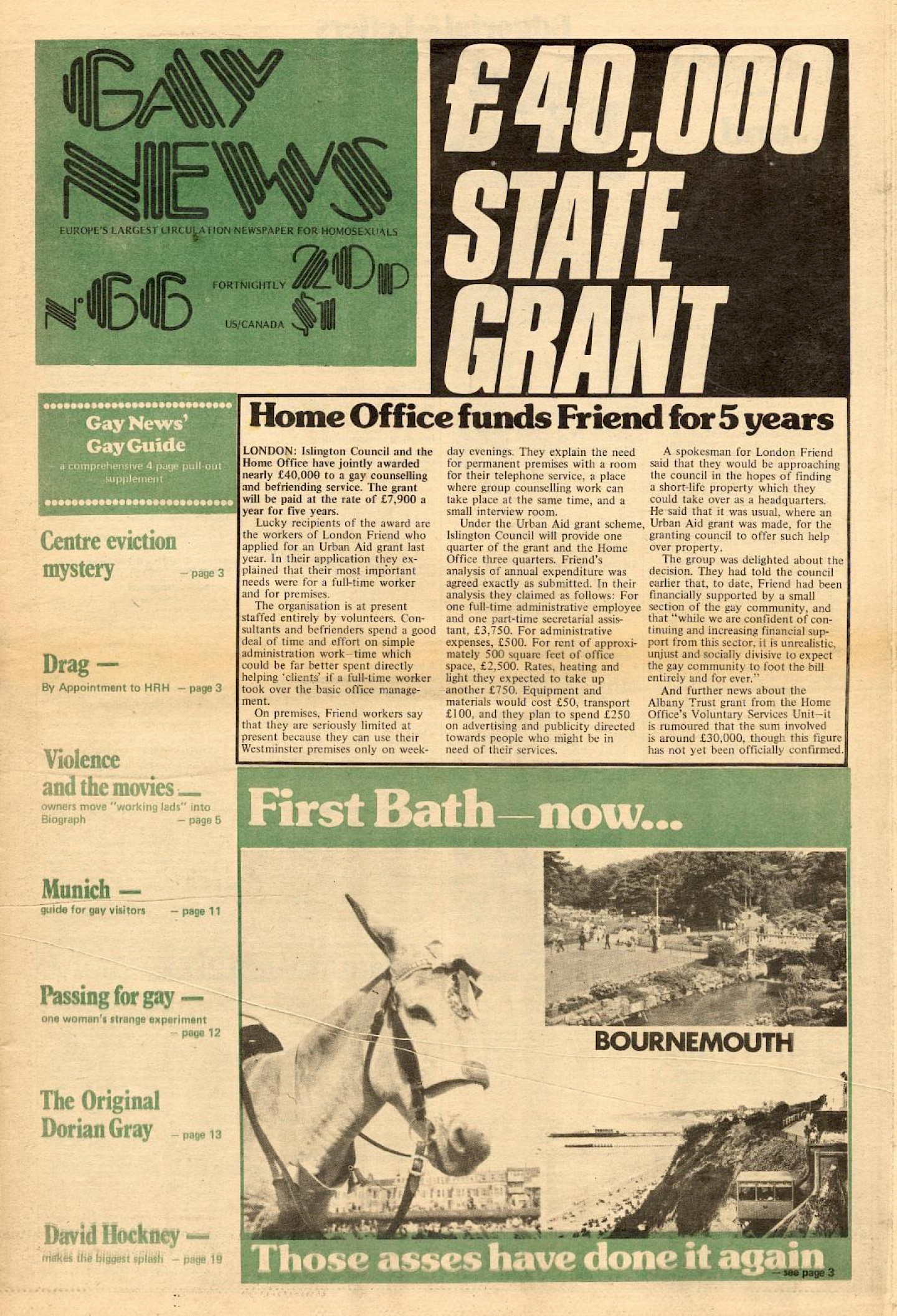

Excitingly, the grant also meant that London Friend were able to move to shop front premises at 274 Upper Street in Islington. Having lost their premises at the Centre in 1973, they had since been working out of group members’ homes. Other smaller - but nonetheless important! - expenditures for things such as equipment, transport, and advertising were covered by the grant. Whilst London Friend, like many other gay organisations, continued to rely on financial support from the gay community, this grant signified an acknowledgment that the gay community deserved access to public funding.

It also enabled London Friend to employ their first paid worker, Roland Jeffery, who was taken on as a full-time paid administrator.

In July 1976, London Friend’s general secretary Roland Jeffery wrote to Mirror Group Newspapers about the possibility of placing an advertisement in the Daily Mirror. In reply Mirror Group sought clarification as to ‘what type of organisation’ London Friend was and also asked to see any literature which explained its services, as well as the text of the proposed advert. The following month they turned London Friend down on the grounds that the advert did not fall into ‘a category … published in the advertisement columns of Mirror Group Newspapers’; the category was not specified. Jeffery’s request for an explanation drew a response from a more senior member of staff at Mirror Group which supported his colleague’s decision. There were, he said, ‘no grounds’ for negotiation.

However, Jeffery appealed again, this time to the editorial director of the Mirror group, who decided that the advert could be published provided it made clear that what Friend offered was ‘help and advice’. Since the relevant letter from Jeffery doesn’t appear to have survived, it isn’t clear what fresh tactics he had employed, but the letter giving news of Mirror Group’s change of heart was copied to Nettie Pollard, Gay Rights organiser at the National Council for Civil Liberties, so it seems likely that she had been asked to advocate on behalf of Friend.

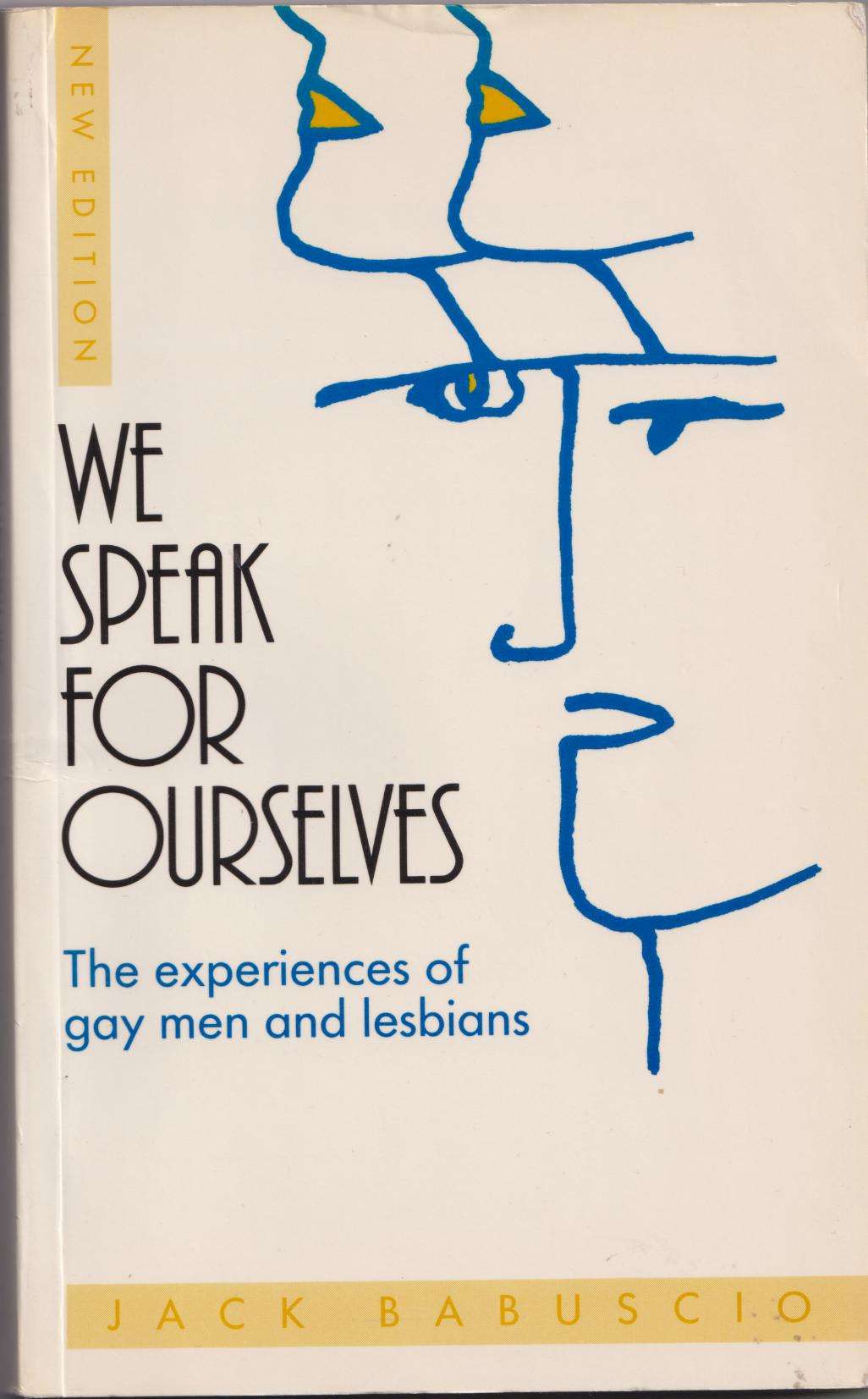

New Yorker Jack Babuscio (1937–90) moved to London in the 1960s. He gradually made a reputation for himself as a historian and film critic, writing mainly for Gay News and, later, Gay Times. He was also a prominent campaigner for equal rights, a counsellor and at one time Chair of London Friend. His best known works are We Speak for Ourselves (published in 1976 by religious publishing house SPCK!), which reflected Babuscio’s experience of counselling, and a much-quoted essay titled ‘Camp and the Gay Sensibility’ (1977).

We Speak for Ourselves was groundbreaking because it emphasised that social service providers and counselling organisations needed to be sensitive to the specific needs of their gay and lesbian clients at a time when, in many instances, they felt unable even to disclose their sexuality. Using case histories and transcripts of counselling sessions, the book set out to show how gay men and lesbians viewed themselves and, in particular, what they saw as the obstacles they faced to full acceptance. Reissued in 1988 with two new chapters dealing with the consequences of the AIDS crisis, it constituted an authoritative handbook for those involved in the counselling of gay men and women.

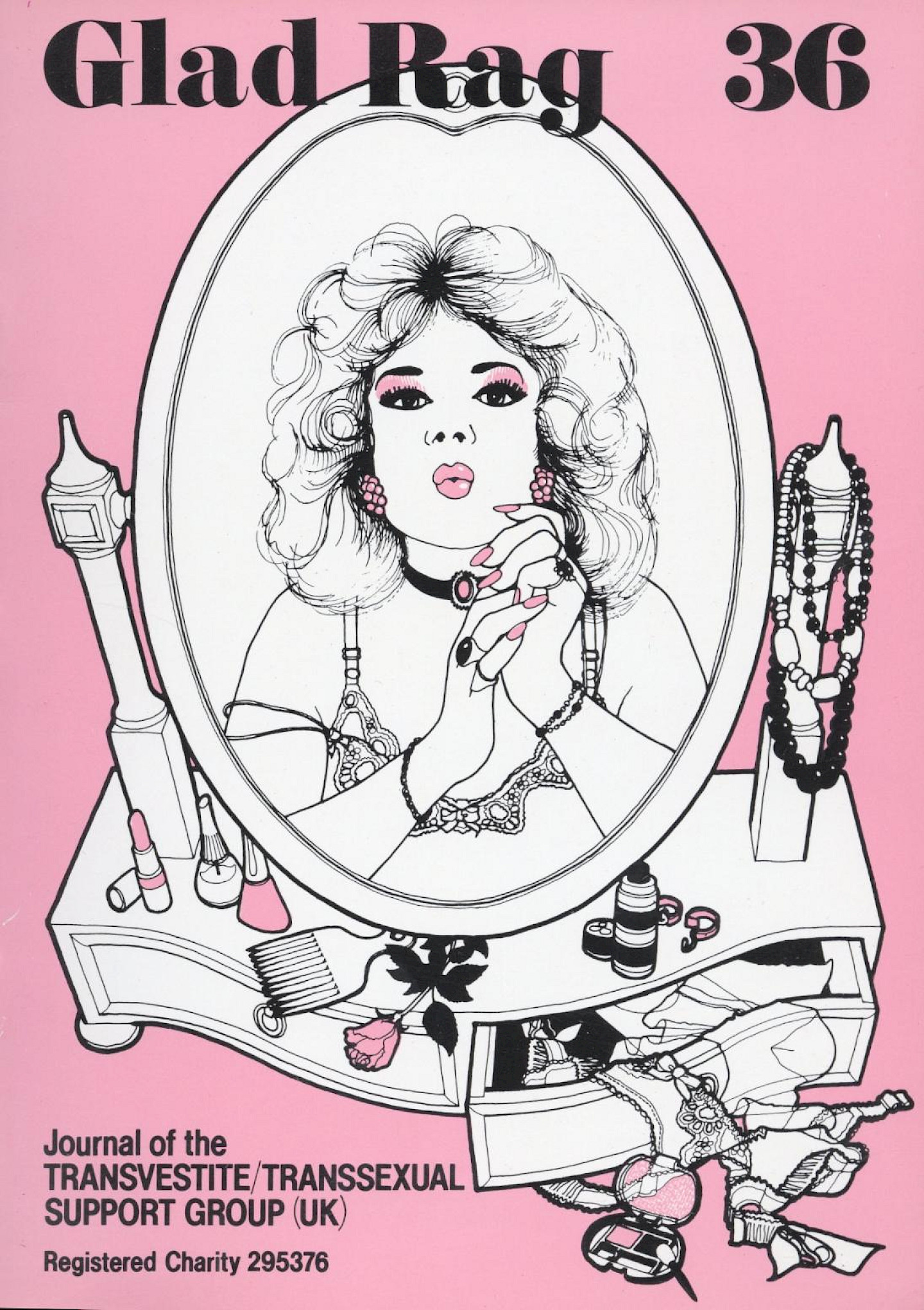

In October 1976, London Friend started making their building available as the regular meeting place for the Transvestite/Transsexual Group, (TV/TS group). London Friend’s 1979 Annual Report described this development as ‘part of Friend’s concern for sexual minorities who are largely not understood and for whom there are few facilities available.’ There were discussions in the Group’s early years about how it could fit within London Friend’s structure, but it ended up functioning as an autonomous user-group with its own membership and journal, and paying a small rent to London Friend for use of its premises.

The group held meetings at 274 Upper Street every Saturday and Sunday (and eventually Friday) evening, which were described as ‘very informal affairs: just a friendly social gathering, although there is always someone to help, counsel, or advise.’ This mixture of socialising and support characterised the Group’s activities over the years, with boat trips, annual “dinner and dances” and a pen-pal service on offer as well as helplines, befriending and a self-published booklet for the partners and families of transvestites.

Whereas the Beaumont Society, a national transvestite group, officially excluded homosexual and bisexual members at this time, the TV/TS Group prided itself on its open-door policy. The Glad Rag reported that most members identified as MTF transvestites but ‘a fair proportion of the balance’ identified as transsexuals. People of all sexualities were welcome, as were ‘Wives, girlfriends [and] friends, in fact anyone with a genuine interest', though the Group appears to have predominantly catered for MTF, rather than FTM, transvestites and transsexuals. During its years at London Friend, the TV/TS group expanded its services and dramatically increased both its membership and reach, securing numerous mentions in the ‘Agony Aunt’ pages of the national press, and distributing its journal, The Glad Rag, nationally (and in some cases, internationally). In doing so, it not only offered a unique weekly opportunity for its members to safely “dress” and socialise together in central London, but also provided support, and a sense of community and belonging, much more widely.

Related Events

In 1975 Friend rented it’s first real home, a former solicitor’s office at 274 Upper Street, Islington. The building had space for meeting rooms, offices and counselling rooms, and would be Friend’s home until rising rents forced it out in 1986.

In 1977 London Friend had a party to officially open their new home and celebrate their 5th birthday. The opening ceremony was meant to be conducted by Maureen Colquhoun, a Labour MP who lived locally. Colquhoun was going to make her coming-out speech at the event, but was advised by her party against doing so and pulled out. (Two years later she was deselected by her local constituency party owing to her sexual orientation and support for women’s rights.) At the eleventh hour Graham Chapman, a gay writer and actor best known for being part of the Monty Python team, was asked to stand in for her. As a prominent campaigner for equal rights, Chapman was happy to do so.

The drama surrounding the opening ceremony illustrates the constraints under which gay individuals and organisations operated in the 1970s.

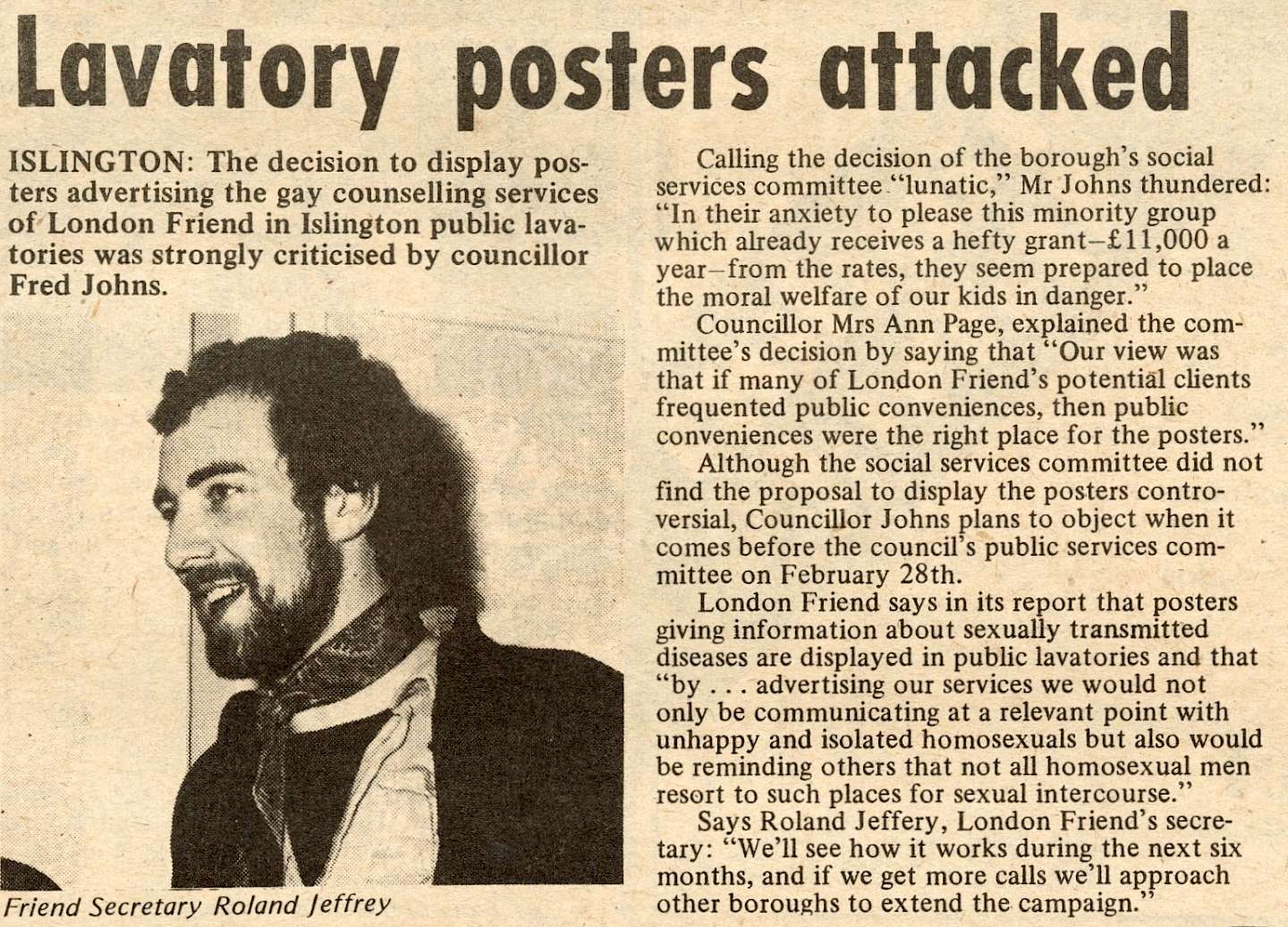

In the mid-1970s Islington Council allowed London Friend to put up posters advertising its services in the borough’s 32 public lavatories. The council had been divided 50/50 over giving permission for the posters, with the chairwoman using her casting vote in favour. But when it came under pressure from the police, who were worried by the fact that the lavatories had been attracting numerous visits from young gay men and also concerned (if it’s to be believed) by the number of attacks sustained by gay men in and around them, the council took the drastic decision to demolish two of the lavatories at a cost of £2,500.

Some councillors blamed the alleged problems on the London Friend posters and it’s tempting to see the decision to demolish the toilets as the revenge of those who had all along opposed London Friend’s efforts. But the council had supported London Friend’s successful application for an Urban Aid grant from the Home Office only the previous year (it was the first government grant to a gay-led organisation), so this decision made the council appear inconsistent as well as irrational. However the incident attracted widespread attention, which will have helped to make London Friend better known.

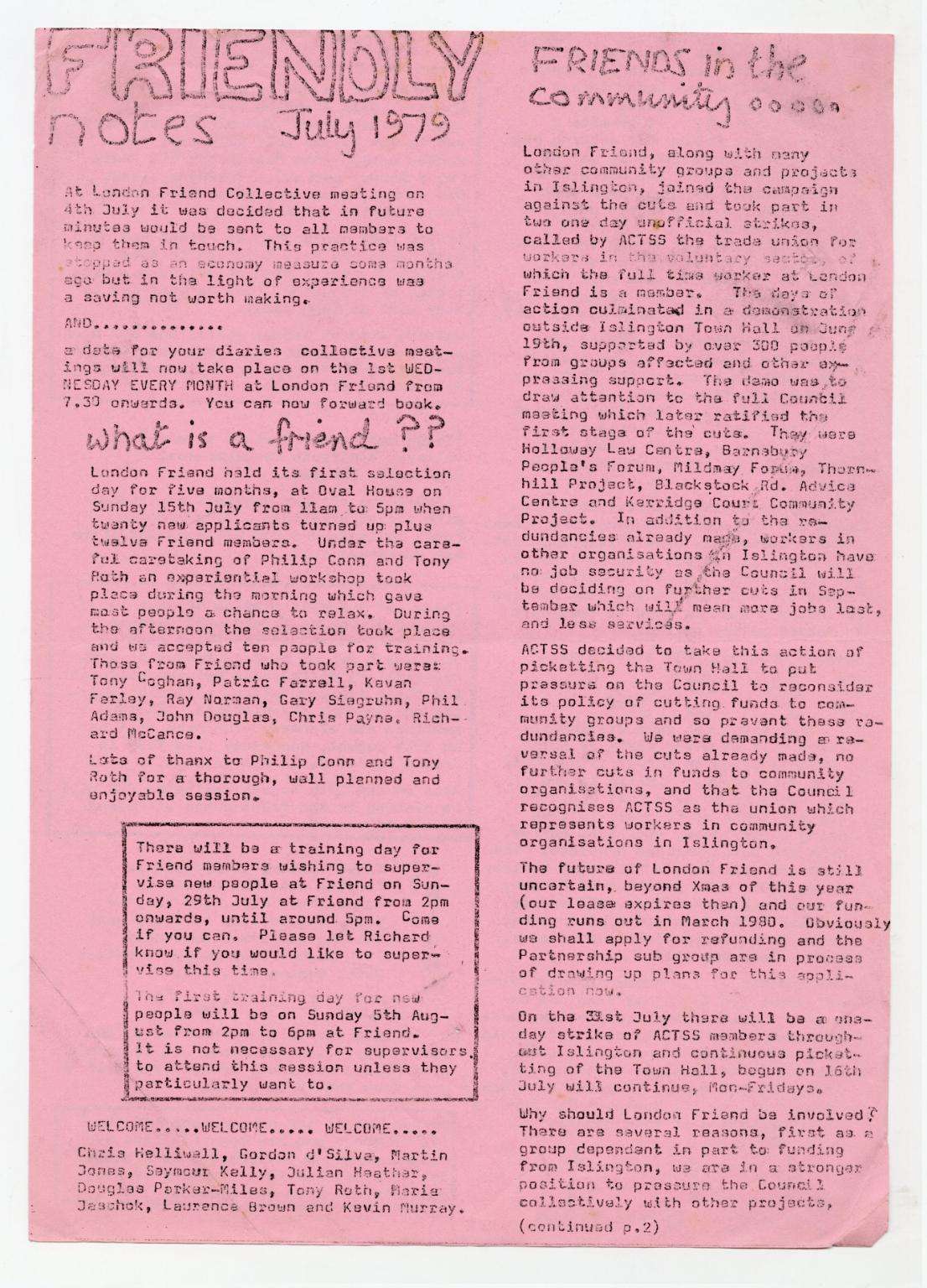

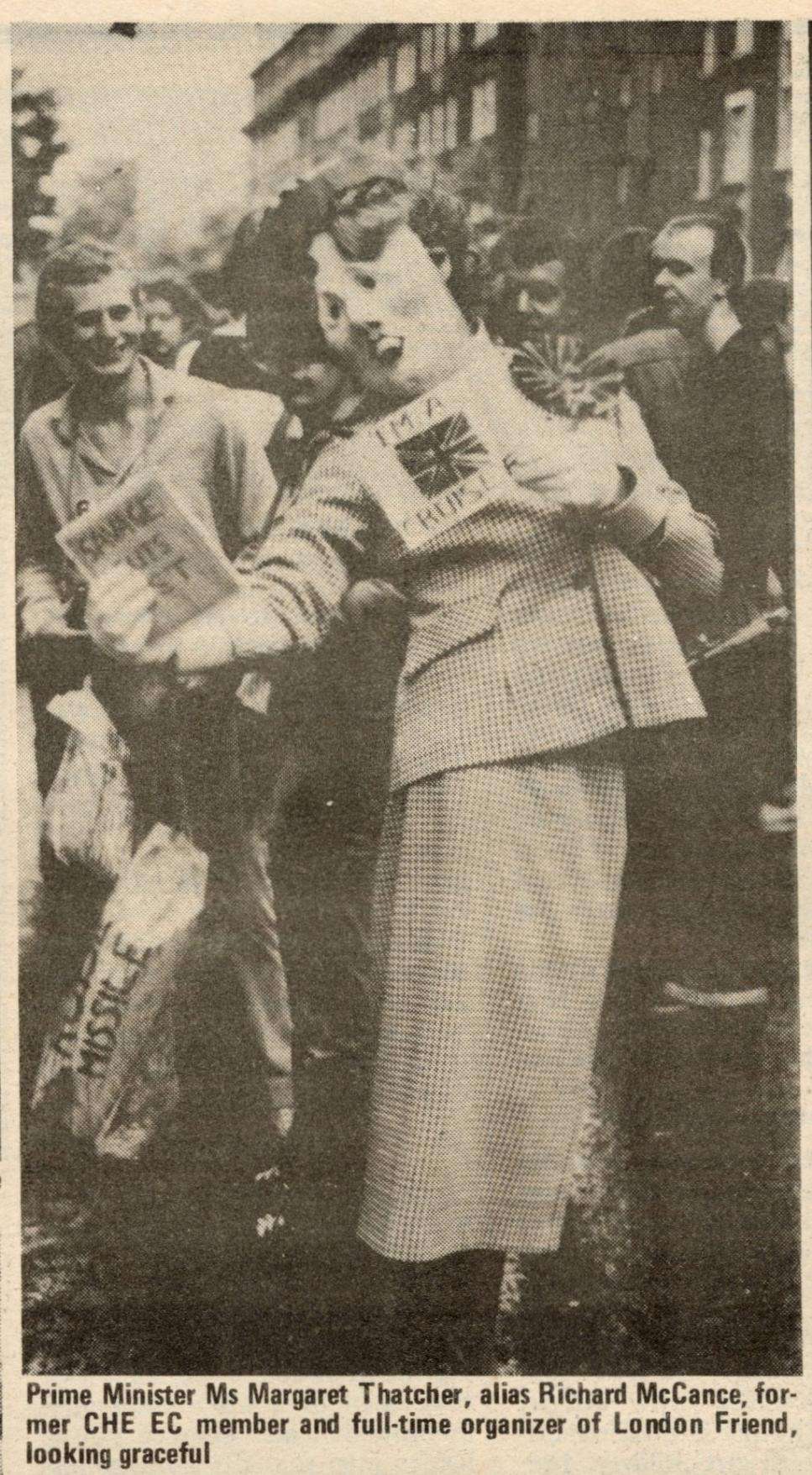

The July 1979 edition of London Friend’s newsletter Friendly Notes details the group’s involvement in a campaign against funding cuts in Islington. London Friend participated in strikes called by ACTSS, the trade union for workers in the voluntary sector, which their full-time worker, Richard McCance, belonged to. In Friendly Notes McCance argued that it was important for London Friend to show solidarity with other groups threatened by the cuts, not only because there was greater strength in collective action, but because it would be a good way to raise awareness of London Friend and its work within the local community. McCance noted that London Friend were about to lose their main funding and needed to reapply. The climate of austerity left London Friend facing an extremely uncertain financial future, dependent once again on fundraising, volunteer labour and financial support from the gay community.

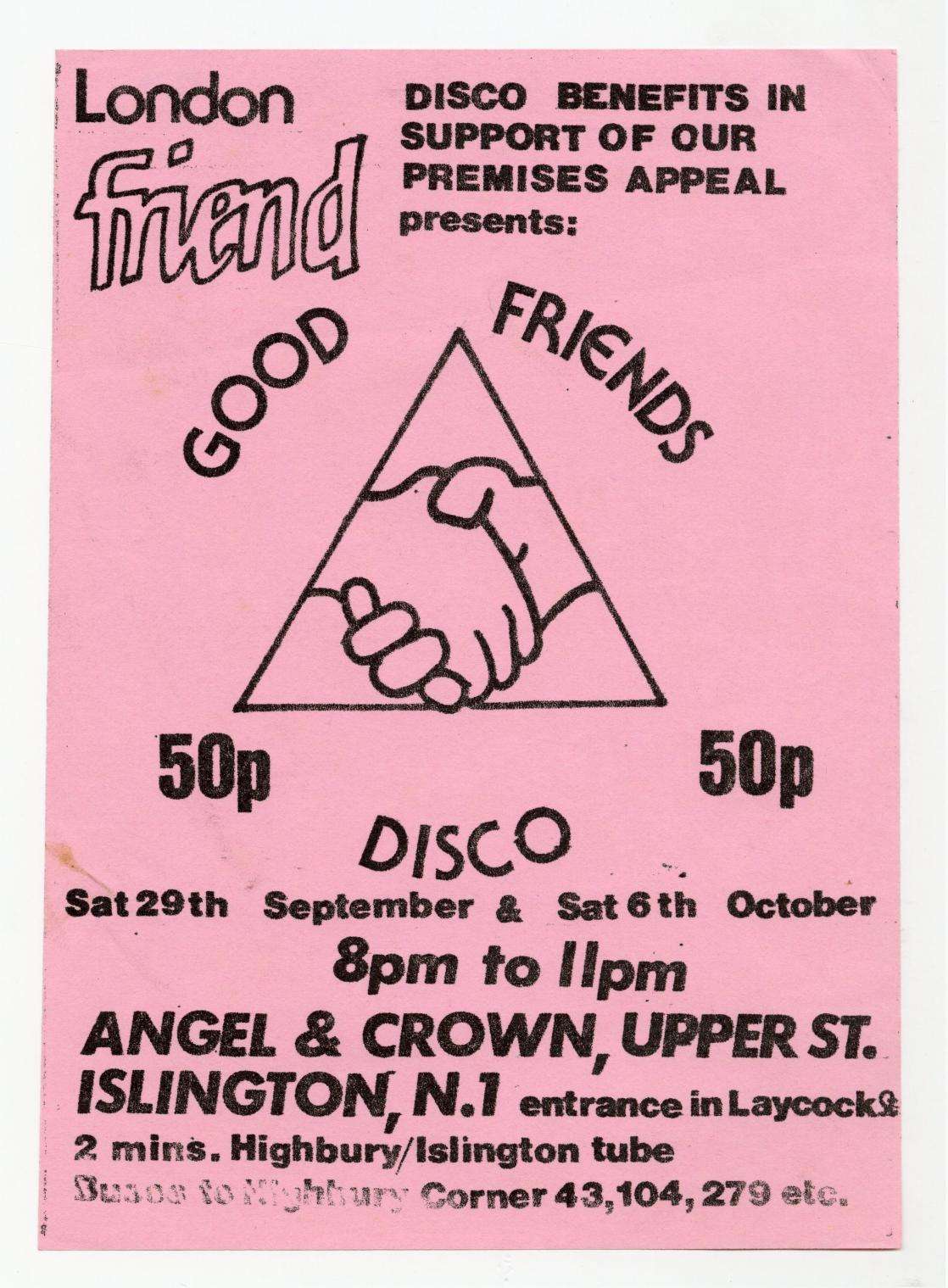

London Friend held three fundraising ‘GOOD FRIENDS DISCOS’ at the Angel & Crown pub, Upper Street, on consecutive Saturday nights between September 29th and October 13th, 1979. They were organised in support of a ‘premises appeal’ that was launched at a point when London Friend’s funding from Islington Council was under threat and their lease at 274 Upper Street was up for renegotiation. The events raised £70 in total, with between 45 and 80 people attending each night. The discos were also chances for London Friend members and service users to socialise and make connections, as well as increase community awareness of the organisation’s work.

Unfortunately, the run of fundraisers ended on a sour note when, according to an internal London Friend newsletter, the pub’s other customers objected to several TV/TS Group members using the women’s loos, and the landlord responded by ruling out any future discos. The landlord suggested he would have been happy with just the gay customers as ‘he did very nicely out of the bar, but London Friend made it clear they would refuse any such arrangement.

London Friend’s Annual Report (1979) described how calls from people identifying as transvestite or transsexual had ‘increased markedly’ since the TV/TS Group’s inception. With this type of call now averaging a fifth of all calls to London Friend, it was agreed at the Collective Meeting held on the 3rd of October 1979 that a new, separate phone line would be installed at 274 Upper Street specifically for the TV/TS Group.

Calls were initially only taken on weekend evenings, during the first part of the Group’s regular social meetings, but this was later expanded to include regular weekday daytimes and a 24-hour answering machine service that was monitored daily and greeted callers with basic information about the organisation.

Whilst the helpline acted for many as a stepping-stone towards visiting the group itself, it was primarily there to ‘listen, give comfort, advice and information’ to callers no matter where they were calling from. Regularly receiving referrals from the likes of the Samaritans and the Agony Aunts of the national press, the line took calls from all over the country. And, as Yvonne Sinclair, the TV/TS Group’s co-ordinator at the time, emphasised in The Glad Rag in January 1983, as the only phoneline specifically for transvestites and transsexuals in the whole of the British Isles, it was the only way that some people living in remote areas could ‘have a good talk with someone like themselves about their ideas, their hopes, their worries or their problems.’

Related Events

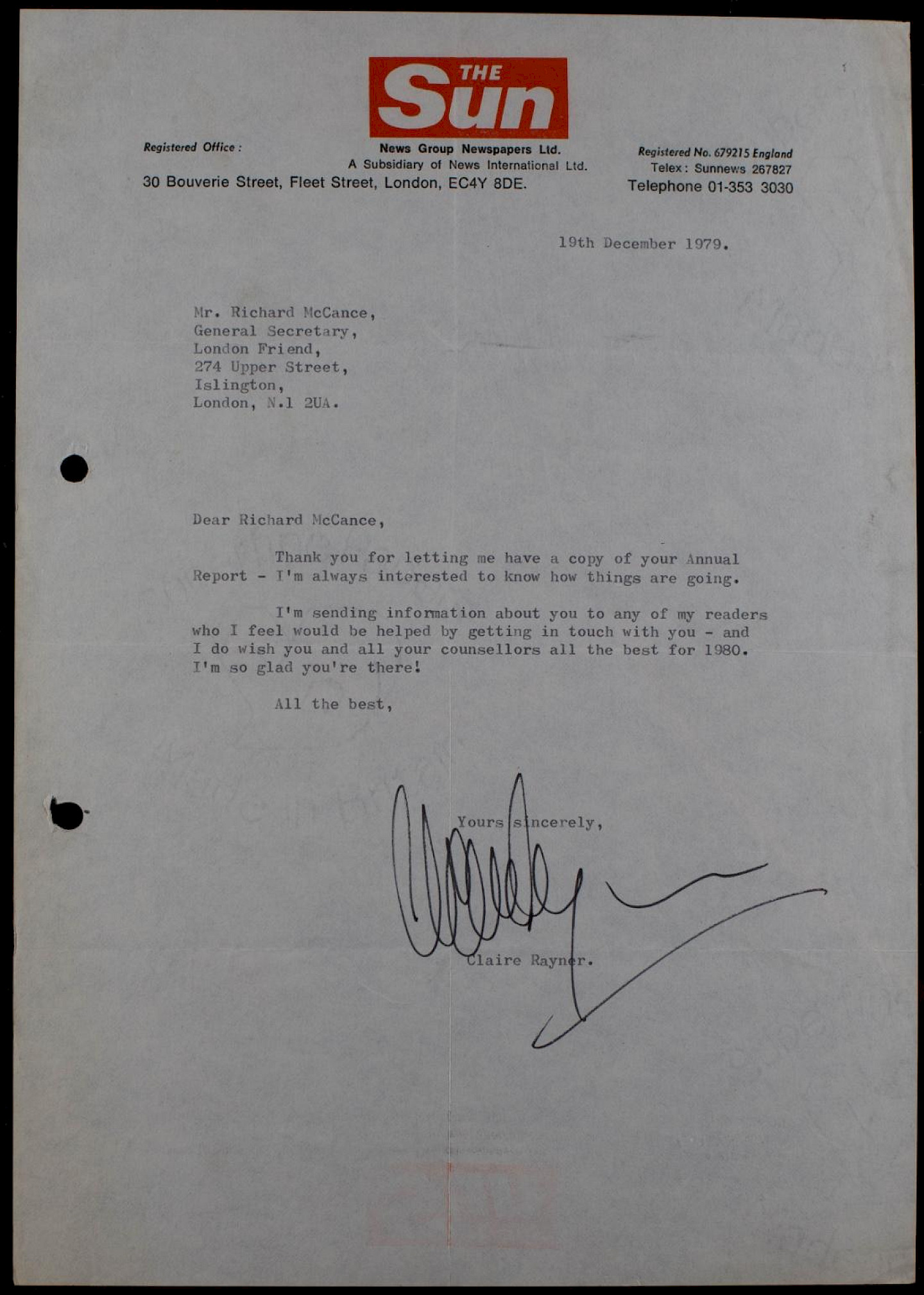

With the possible exception of Marjorie Proops, Claire Rayner (1931–2010) was the twentieth century’s best known agony aunt. Having trained as a paediatric nurse, she regarded it as her job to educate and inform as well as give advice. In 1973 she started working for The Sun, where she succeeded in persuading the management that she ought to answer letters from men as well as women. Her capacity for work was remarkable—which was just as well, considering that in the week that she dealt with premature ejaculation she received 18,000 letters! Fortunately, she had six secretaries and a research assistant.

Rayner was a great supporter of Friend’s work. On 19 December 1979 she wrote to Richard McCance, general secretary of Friend, to thank him for sending her a copy of Friend’s annual report and assuring him that she sent full details of Friend to any reader who she thought would benefit from its services. Her letter concluded, ‘I’m so glad you’re there!’ In 1985 she was made an honorary member of Friend’s TV/TS group, which resulted in a huge surge in membership.

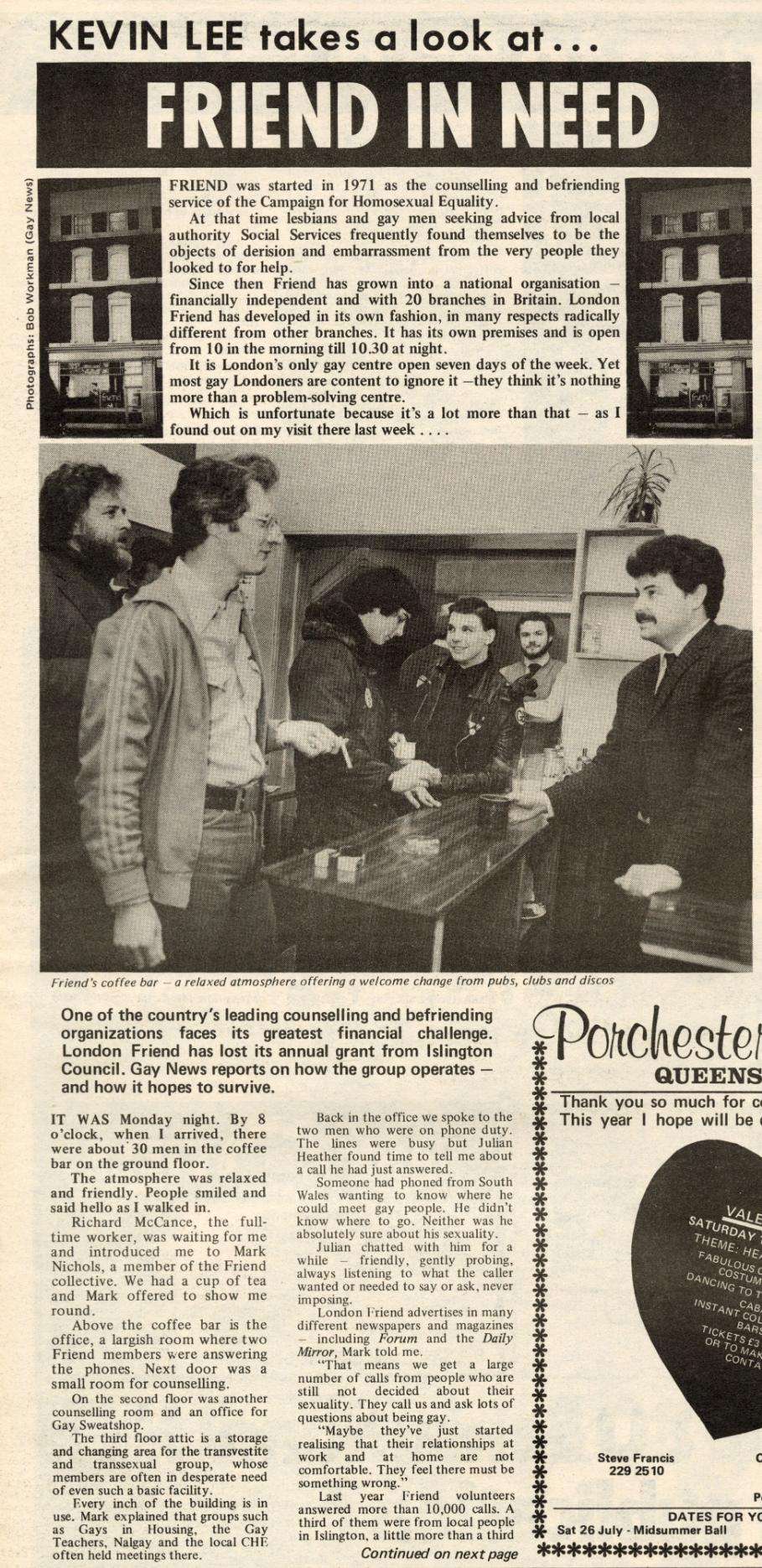

FRIEND was started in 1971 as the counselling and befriending service of the Campaign for Homosexual Equalty.

At that time lesbians and gay men seeking advice from local authority Social Services frequently found themselves to be the objects of derision and embarrassment from the very people they

looked to for help.

Since then Friend has grown into a national organisation financialy independent and with 20 branches in Britain. London Friend has developed in its own fashion, in many respects radically

different from other branches. It has its own premises and is open from 10 in the mornin til 10 30 at night.

It is London's only gay centre open seven days of the week. Yet most gay Londoners are content to ignore it - they think it's nothing more than a problem-solving centre.

Which is unfortunate becauce it's a lof more than that - as I found out on my visit there last week ...

London Friend’s Urban Aid grant was discontinued in 1980. Partly to blame was Islington Council, who advised the grant’s administrators, the Inner City Partnership, not to renew it.

A London Friend member, Paul Hoddinott, described this decision as a ‘political move’ by the ‘right wing’ of the Labour Party who were, in his opinion, cutting Friend’s grant to ‘settle old scores’ with the left. The loss of London Friend’s funding occurred in the context of funding cuts to many other community services and organisations in Islington

London Friend would now once again be totally reliant on volunteer labour for a few years. In 1980 the volunteer collective were feeling up to the challenge. They told Gay News that the Transvestite / Transsexual Group’s phone line was ‘the first of its kind in the country,’ their group for married men was going very well and they had plans to open late on Friday nights so people could drop in after the Icebreakers disco nearby.

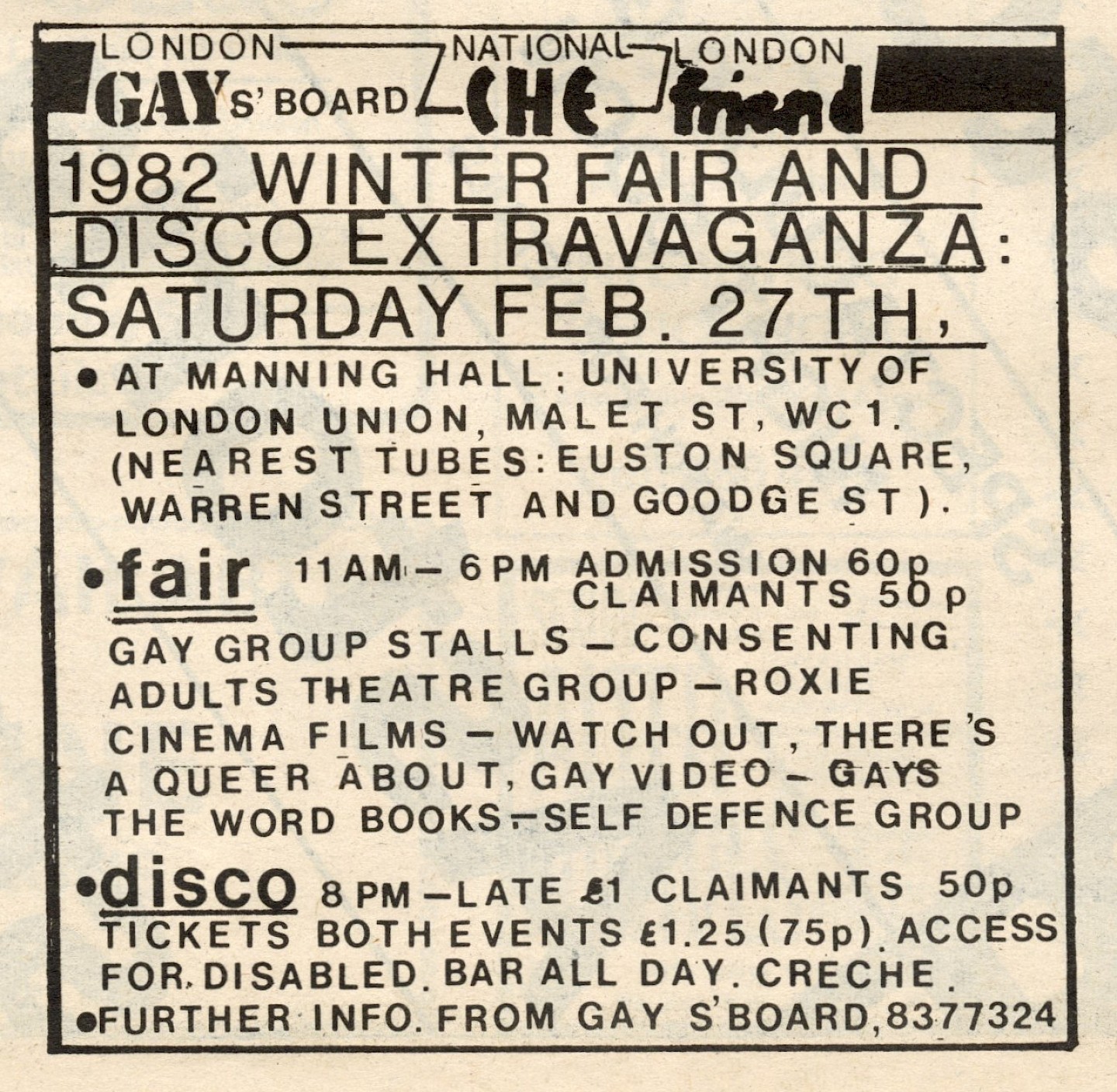

1982 winter fair and disco extravaganza: Saturday february 27th.

At Manning Hall; university of London union, malet st, WC1.

Fair: Gay group stalls - consenting adults theatre group - Roxie cinema films - watch out, there's a queer about, gay video - gay's the word books - self defence group.

Disco: tickets both events 75p. Access for disabled. bar all day. creche.

On Saturday 27 February 1982 London Friend, joined forces with London Gay Switchboard and the Campaign for Homosexual Equality to hold a Winter Fair at the University of London Students’ Union building in Malet Street. The day culminated with a ‘Disco Extravaganza’ in the evening.

In addition to the stalls staffed by a variety of organisations and businesses, there was plenty of entertainment on offer: gay theatre group Consenting Adults in Public gave a performance, there was jumble, video games and swimming, but ‘the undoubted hit of the day’, Capital Gay reported, was a showing of Gay Video Project’s hilarious spoof police training film Watch Out: There’s a Queer About! It was estimated that the event drew around 1500 people—and, on top of the publicity it generated, around £1000 was raised for the three organisations.

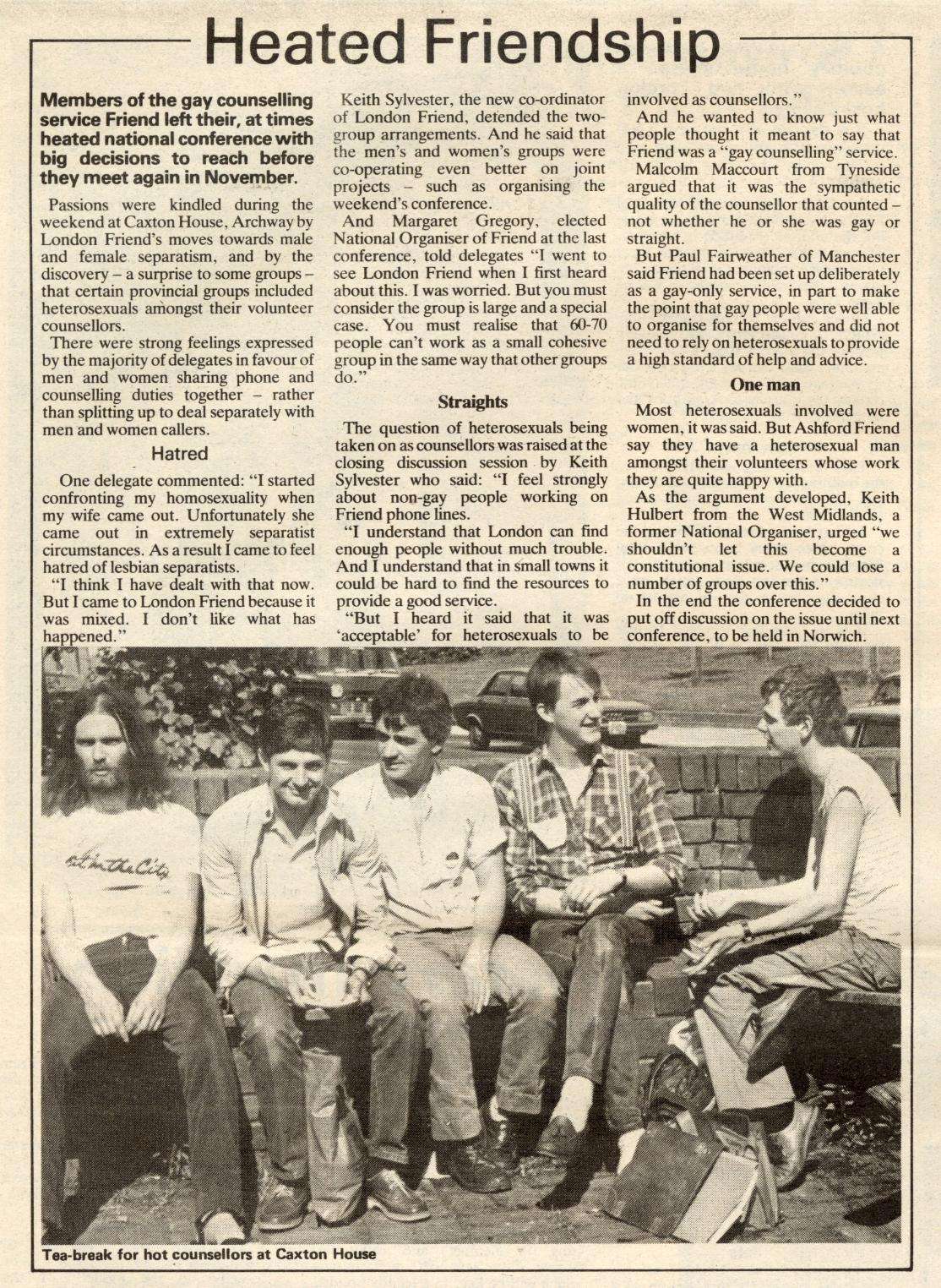

Member of the gay counselling sevice Friend left their, at times heated national conference with big decisions to reach before they meet again in November.

Passions were kindled during the weekend at Caxton House, Archway by London Friend's moves towards male and female seperatism, and by the discovery - a surprise to some groups - that certain provincial groups included heterosexuals amongst their volunteer councellors.

There were strong feelings expressed by the majority of delegates in favour of men and women sharing phone and counselling duties together - rather than splitting up to deal separately with men and women callers.

The Friend National Conference, held at Caxton House, Archway in the summer of 1982 was described in Capital Gay as ‘heated’. London Friend’s use of separate men’s and women’s groups had sparked passionate debate over perceived moves ‘towards male and female separatism.’ According to Capital Gay, most delegates were firmly against male and female volunteers working apart from each other to respond to callers of their own gender, but Margaret Gregory, National Organiser of Friend, told the conference that she viewed London Friend as a ‘special case’: ‘You must realise that 60-70 people can’t work as a small cohesive group in the same way that other groups do.’ London Friend’s coordinator, Keith Sylvester, also reassured the conference that the male and female groups were working together—and, indeed, doing so better than before—on joint projects.

The conference also debated whether Friend groups should be employing heterosexual counsellors, which were seen by some delegates as more necessary in smaller towns with fewer resources to hand. Friend was grappling with the complexities of running a national organisation comprising numerous regional groups, finding that working methods that suited a large metropolis like London might not work for a smaller regional group, and vice versa.

Prime Minister Ms Margaret Thatcher, alias Richard McCance, former CHE EC member and full-time organizer of London Friend, looking graceful.

For a couple of years Friend was forced to rely entirely on volunteer labour after its historic Urban Aid grant expired in March 1980. It received a small deficit grant from the GLC in the early 1980s, and then in 1983 the GLC awarded it a grant to pay for two part-time development workers for one year. This was subsequently renewed for a further year. The GLC also assisted Friend with its running costs.

There was one serious drawback to this situation, which is that the GLC’s own future was in doubt. Friend pledged in 1983 to campaign against the GLC’s abolition by the Thatcher government. Unfortunately, in 1985 Parliament succeeded in narrowly passing the legislation that abolished the GLC with effect from 31 March 1986. This was the start of a low point for Friend, financially speaking.

In 1986 its premises in Upper Street were sold twice, with both buyers raising the rent to a level Friend could not afford. However, after a short stay in offices on Seven Sisters Road, Friend was able to start renting its current home at 86 Caledonian Road, with financial assistance from Islington council.

In 1983 a member of staff from London Weekend Television (LWT) approached London Friend, offering a chance to broadcast a Public Service Announcement (PSA) on London Friend’s services. Throughout 1983, minutes from London Friend’s meetings depict the development of the form and script of this PSA, negotiated by Janet Chambers, one of London Friend’s development workers at the time.

In May 1983, the IBA (Independent Broadcasting Authority) announced they would not allow London Friend’s PSA to be shown. Their primary justification for doing so was their argument that public feeling on gay people was too deeply divided. Notably, the IBA cited the small number of complaints it received following a locally televised PSA from Leicester Gayline-Friend as evidence. Commenting on the situation, National Friend countered that the Leicester Friend’s PSA had been highly successful, resulting in several thousand contacts being made by the group.

The IBA claimed that gay people should not be counselling other gay people, as they would lack the impartiality required for counselling. IBA’s refusal highlighted the difficulty London Friend faced in publicising its activities outside of gay media, and the extent to which gay people’s authority on their own lives and needs continued to be called into question.

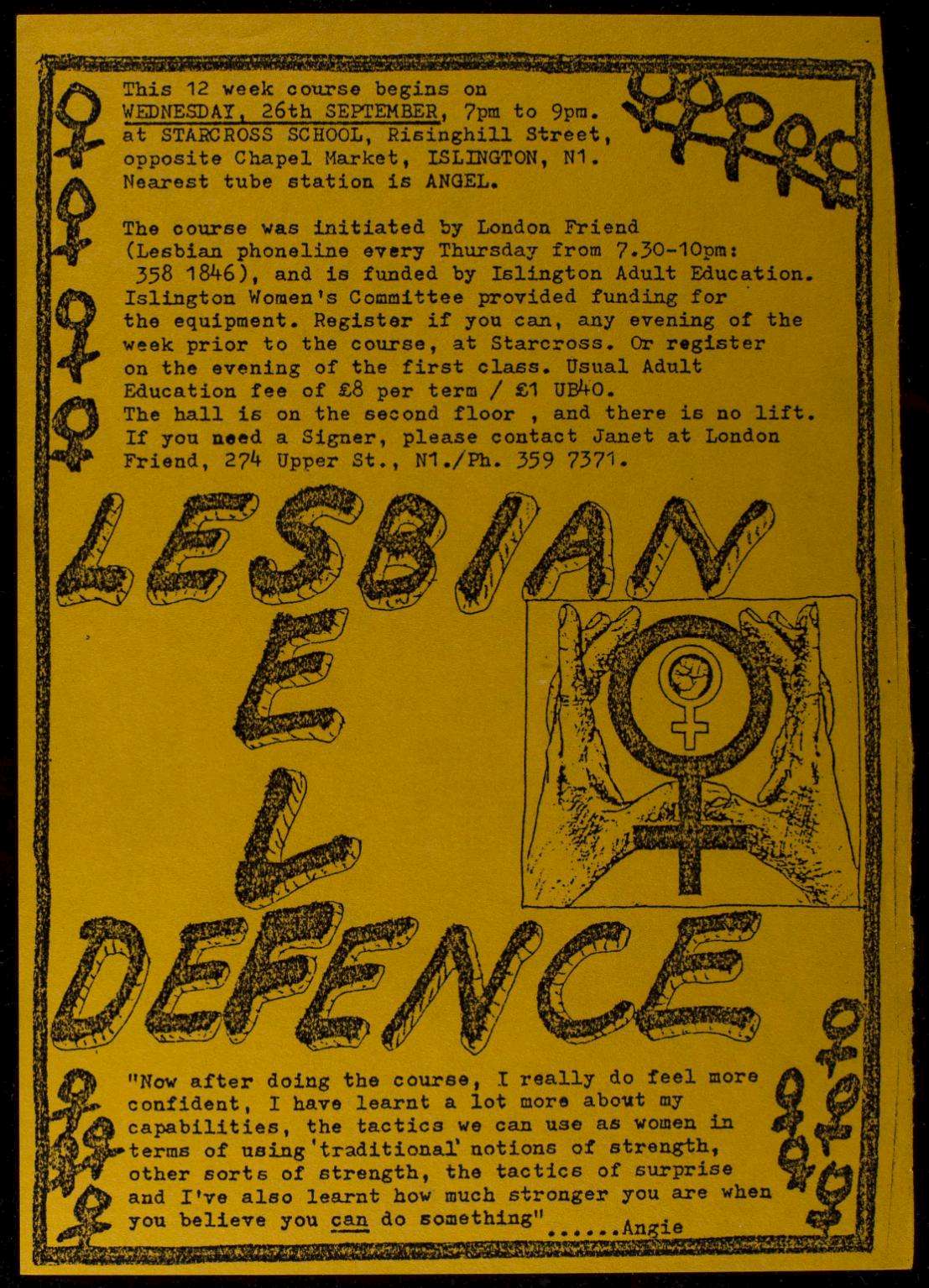

This 12 week course beings on Wednesday, 26th September, 7pm to 9pm at Starcross School, Risinghill Street, opposite Chapel Market Islington N1. Nearest tube station is Angel.

The course was initiated by London Friend, and is funded by Islington Adult Education. Islington Women's commitee provided funding for the equipment. Register if you can, any evening of the week prior to the course, at Starcross. Or register on the evening of the first class. Usual Adult Education free of £8 per term.

In 1983 the group Lesbians at London Friend started a 12-week course in self-defence for lesbians, funded by Islington Adult Education, with equipment provided by the council’s Women’s Committee. The first meeting was held on September 26th, 1983, and involved learning self-defence techniques and discussing how to deal with potentially violent situations. Their leaflet quotes a woman saying, ‘I’ve also learnt how much stronger you are when you believe you can do something.’

In 1982, London Friend had learnt from their mixed Gay Self-Defence group that women and men were attacked in different ways and therefore needed specially tailored self-defence training.

However, the lesbian self-defence course proved to be one of the most controversial groups hosted by London Friend. Within National Friend, the women-only group raised some concerns about ‘seperatism’ at the London branch. Criticising the group’s funding from Islington Council, the Islington Gazette wrote in May 1983 that even Lambeth hadn’t gone so far as to buy ‘lesbians mats for their self-defence course.’

At the time, Lesbians at London Friend was one of the only groups for lesbians in London. As well as the self-defence group on Monday evenings, they offered confidential counselling services on Thursdays and a women’s helpline on Thursday evenings. The self defence group was later described in London Friend’s annual report (1983) as being successful and as expanding the ‘traditional remit of gay self-help.’

In 1983 there was an opportunity to develop projects for Black women and older women in Islington that would be funded by the Women’s Committee in Islington Council. London Friend responded by planning a day conference for older and elderly lesbians that would help to define their needs and issues.

However, London Friend was not given funding by Islington Council to work with older lesbians, partly because of the bad publicity the council had received for funding the lesbian self defence project. Luckily, they were able to keep going with funding from the GLC.

The conference was held on 24 March 1984 and was attended by over sixty older lesbians. It included numerous workshops, readings from authors and ended with a disco. After the conference, attendees produced two written reports - one intended for women only, and one for a wider audience. This report was distributed to over 500 different individuals, voluntary and statutory organisations. Recommendations from the conference included that there should be representation of older lesbians on policy-making committees, there be more meeting places for older lesbians and that the issues surrounding bereavement for older lesbians become better known by health and social care workers.

The Older Lesbians Network developed out of the conference. Older lesbians didn’t feel like there was an existing group that suited them well. ‘Older’ was self-defined and there was no specific age range advertised. The conference report concluded ‘we are here to stay, our numbers are increasing … as we make our voice heard, and take our rightful place in society, everyone will be better off, and we will live in a more tolerant, a more healthy and a more truthful society.’

Are you lesbian or gay?

Unemplyed. Working part time. Retired. Work in Islington, spend your lunch time at Friend.

We serve tea, coffe and fruit juice. Soup sandwiches and snacks all at reasonable prices or bring your own.

Come along, a chance to meet other people, share ideas, talk over the problems of being unemployed.

Now open every weekday from noon 'till three! Thursday, women only.

In early 1984, as unemployment climbed to almost 12%, London Friend announced they would open the doors of 274 Upper Street on Monday and Tuesday lunchtimes. The idea was to provide ‘cheap and friendly’ daytime facilities for unemployed gay people, shift workers, retirees, and other locals who might be free during the day. Tea, coffee, fruit juice, soup, sandwiches and snacks were available ‘at reasonable prices’, or attendees were welcome to bring their own. The service was later expanded to every weekday from midday until 3 pm, with Thursdays being for women only. Utilising its central London premises to adapt to the challenges of the time, these ‘Lunchtimes at London Friend’ sought to offer affordable facilities, social contact, and the opportunity to discuss shared situations, to groups of people who may well have been experiencing isolation.

In January 1985, National Friend produced a discussion document entitled 'AIDS and Friend'. It was clear that as one of the self-help organisations serving the LGBTQ+ community, 'Friend must formulate its own guidelines on the implications of AIDS and determine what other reponses to initiate.' Friend were grappling with how their work needed to adapt to the growing AIDS epidemic: did they need to mention AIDS in every conversation with callers? When sex was mentioned did they need to encourage the caller to think about safe sex? How could they balance keeping people safe with their core mission to reduce the stigma and shame associated with homosexuality? They expected to see growing numbers of people calling their helplines about AIDS, both those directly affected and the 'worried well.’

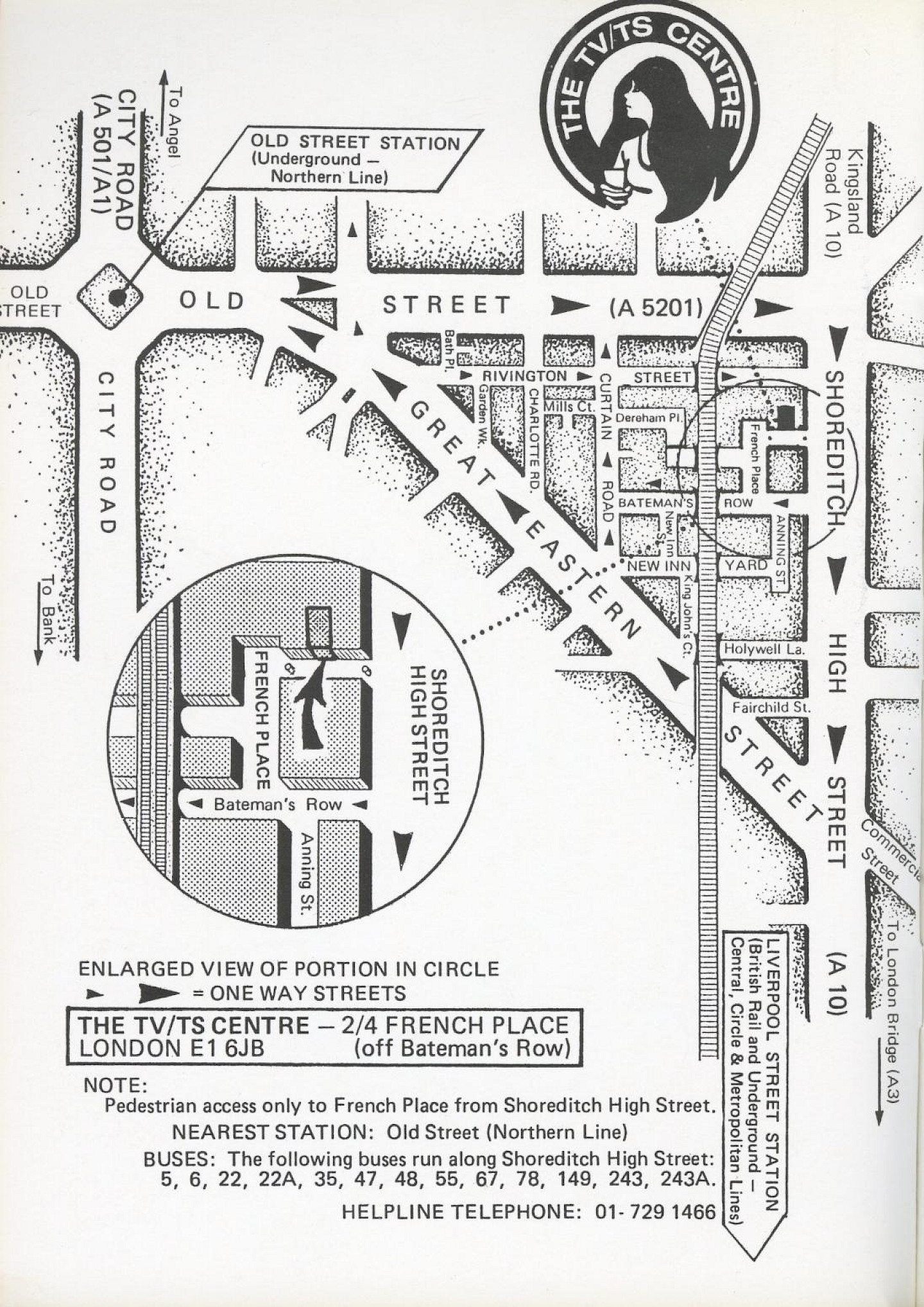

On June 1st, 1986, the Transvestite/Transsexual Group held its final social meeting at 274 Upper Street before moving to its own rented premises and effectively separating from London Friend. Though precipitated by London Friend’s own lease coming to an end, this move was an eventuality for which the Group had long prepared. As a sub-tenant to an organisation itself dependent on grants or outside funding, their position at London Friend was always felt to be ‘tenuous at best’. Fearing they wouldn’t be offered the same welcome (or ‘peppercorn’ rent) by other gay organisations, the Group decided in 1982 to form a paid membership to start raising funds for its own premises.

The new TV/TS Centre, which opened its doors at 2-4 French Place, Shoreditch on July 5th, 1986, was described by Yvonne Sinclair, the Group’s co-ordinator, as the country’s first ever centre run both for and by transvestites and transsexuals. It was the remarkable growth of the TV/TS Group during its time at London Friend that made this possible – shortly before the move, its building fund had reached £8758.55, and the 1986 Annual General Meeting reported that the group was fast approaching 1000 members. As The Glad Rag put it on the first anniversary of the TV/TS Centre’s opening, ‘During its formative years, the TV/TS Group had the good fortune to have the use of 274 Upper Street, by the courtesy of London Friend; their hospitality, welcome and help enabled The Group to become the strongest in the country. We owe London Friend (and the Gay Community countrywide) our gratitude for their tolerance and co-operation, when the “normal public” offered us little.’

Few people have had such a wonderfully varied and colourful, not to say rainbow-coloured, career as Michael Cashman, former volunteer and current patron of London Friend. Having been a child actor, he made his television debut at the age of fourteen in the ITV series Gideon’s Way and at seventeen appeared in the National Youth Theatre’s groundbreaking production of Peter Terson’s Zigger Zagger. As an adult he has had a long and successful acting career, mainly in television supporting roles, although he co-starred with Ian McKellen at the National Theatre in Martin Sherman’s Bent (the first full-length play about the Nazis’ persecution of homosexuals) to great acclaim.

It’s arguable, though, that his greatest claim to fame is that, as Colin Russell, the first gay character to be featured in the BBC soap opera Eastenders, he kissed his younger boyfriend—on the forehead! This was the first gay kiss ever seen on British television. It was the autumn of 1987, and it caused the right-wing press to react with homophobic fury. It was bad enough that there were gay characters in the show at all: when their appearance had been trailed the previous year, The Sun had complained that Eastenders was turning into Eastbenders. (Questions were even asked in Parliament.) Two years later Colin and his new boyfriend, Guido, provoked a similar outburst by kissing each other, this time on the lips.

In 1989 Cashman co-founded Stonewall, initially in protest at the introduction of Section 28. From 1999 to 2014 he was a Labour MEP for the West Midlands, speaking on human rights. In 2013 he was awarded the CBE for his services to the cause of equality, and the next year became a life peer, taking the title Baron Cashman of Limehouse. He has continued to campaign vigorously against discrimination against minorities, both at home and abroad.

Cashman’s autobiography One of Them: From Albert Square to Parliament Square was published by Bloomsbury in 2020 and was nominated for a number of prizes.

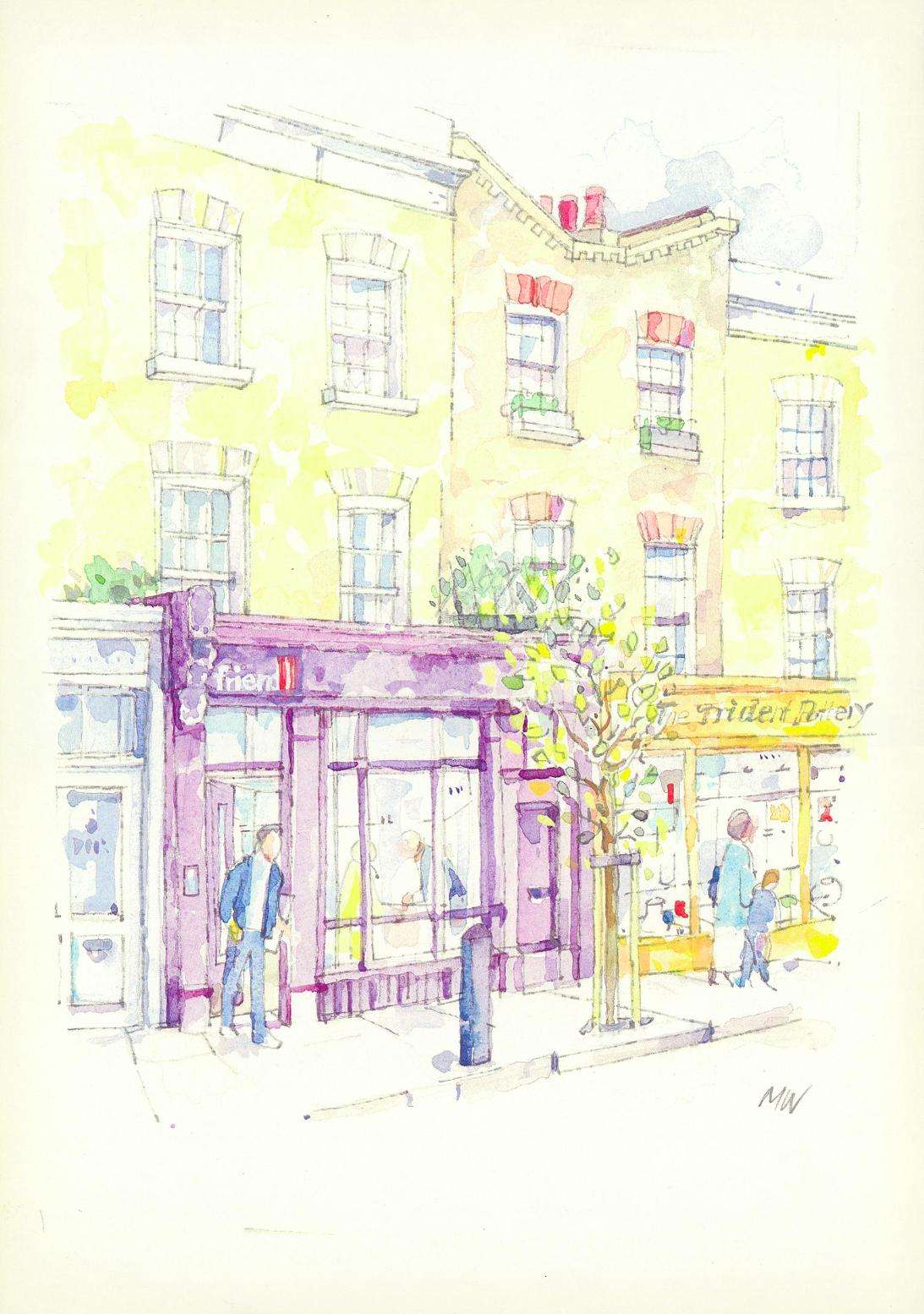

London Friend gained access to their new, permanent home at 86 Caledonian Road in 1987. On 31 March 1988 the building was fully operational, and London Friend had signed a twenty-year lease. This move came after a period of instability for London Friend; the rent of their previous premises in Upper Street had been raised to a level they could not afford and they had temporarily worked from offices in the Seven Sisters Road as a result. London Friend rented 86 Caledonian Road from Islington Council - until 2011 when they were able to buy the freehold.

Now in their own, secure home, London Friend reflected that that their move, at a time when the LGBTQ+ community were facing challenges from both AIDS and Clause 28, had given them the ‘duty’ of developing into a ‘bigger and more effective organisation.’

Gay newspaper, Capital Gay, reported that 86 Caledonian Road was a ‘cleaner, bigger and better’ centre for London Friend, with a coffee-bar, a face-to-face counselling room, phone-in facilities and a large meeting room. Significantly, this new location also had central heating and disabled access, London Friend had worked with GEMMA and Gay Men’s Disabled Group to make the first floor wheelchair accessible.

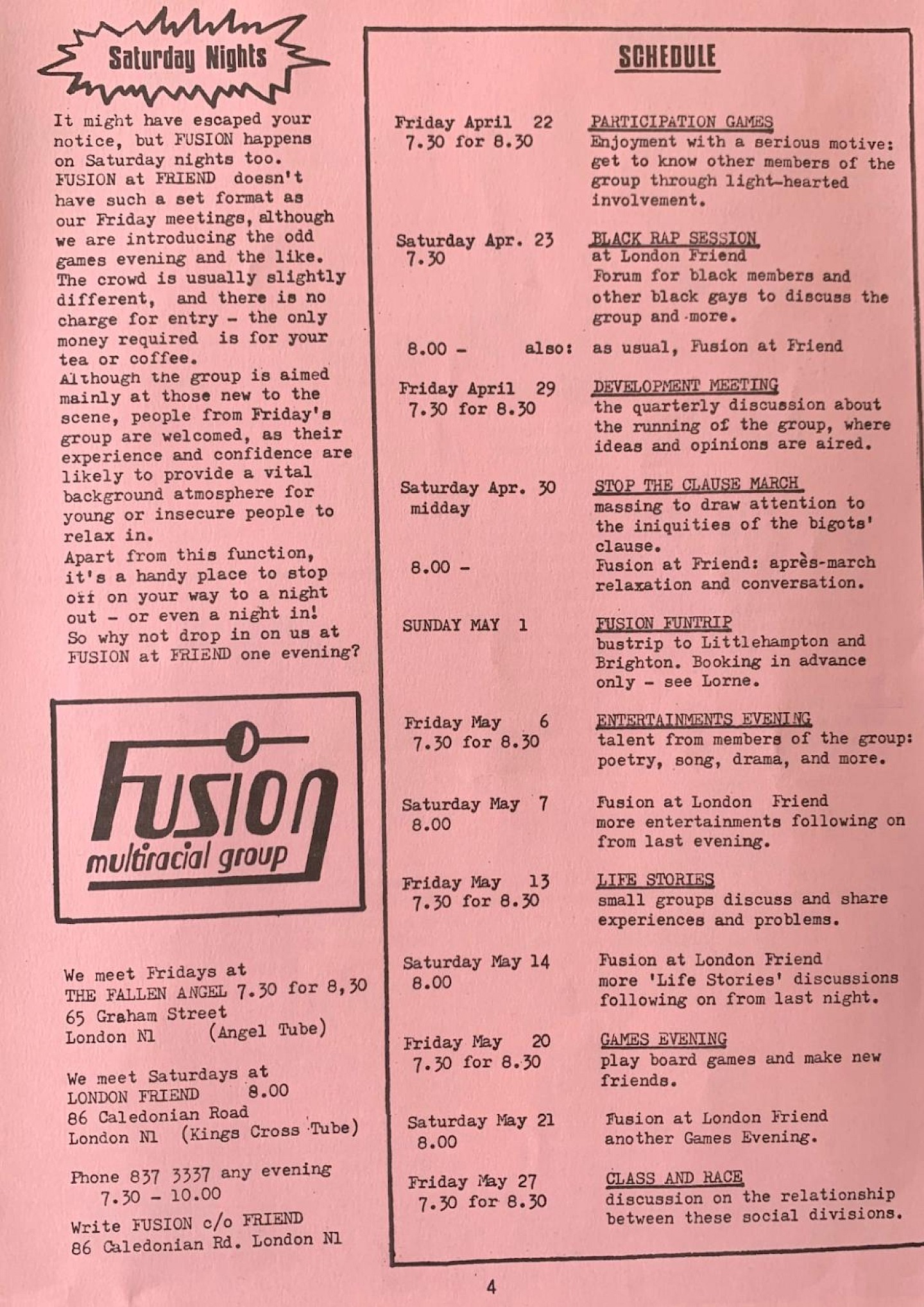

Fusion, a ‘multi-cultural, multi-racial’ social and support group for gay men, began meeting on Saturday evenings at London Friend, early in 1988. Billed as ‘London’s friendliest multi-racial group for gay men’ and, like all of Friend’s groups, an alternative to the commercial scene, Fusion aimed ‘to bring together men of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds to meet for mutual learning and understanding, and to explore each other’s needs and problems.’ The organising committee, known as the Nucleus, initially consisted of a co-ordinator and six other representatives of the group, but by 1993 the post of co-ordinator had lapsed and membership of the Nucleus had expanded to eleven.

Behind the quizzes, videos, board games, social evenings, coach trips to Brighton and all the rest lay a deeply serious purpose: to facilitate the forging of genuine friendships across racial divides. For this reason those who ran the group were more than usually concerned to discourage users from coming to meetings with a view to making connections of a purely or largely sexual nature. (At one meeting of the Nucleus, it was lamented that the atmosphere at meetings was sometimes ‘cruisier’ than was thought desirable.) The leadership also had, for the late ’80s and early ’90s, an exceptionally enlightened perception of what constituted unconscious racism, and were adamant that it would not be tolerated within the group.

Fusion also spawned Fusion Hispanica, a social group for Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking gay men, which had its own separate meetings at a Kings Cross pub on the third Saturday of each month but which, to all intents and purposes, merged with the parent body on the other Saturdays.

London Friend

Counselling for Lesbians and Gay Men by Lesbians and Gay men. Annual Report 1988/89.

Funded by London Boroughs Grants Scheme.

With the move to their new, bigger home in Caledonian Road, came a concerted effort from London Friend to extend their services to a wider range of service users. In 1988, Friend drafted and agreed on an Equal Opportunities Policy; aiming to ‘emphasise [their] commitment to providing caring and worthwhile services to all lesbians and gay men.’ In practice, this meant recruiting volunteers who were women and people from Black and ethnic minority communities, all groups who were under-represented at London Friend. This was done by strategically publicising Friend’s services to these groups in particular, holding in-service training days for volunteers to learn about specialist services for lesbian and gay ethnic minority communities and hosting or forming new groups at London Friend such as Onyx, a social, discussion group for black lesbians and lesbians of colour and Shakti, a South Asian lesbian and gay organisation.

London Friend’s February 1989 newsletter reported more women and people from Black and ethnic minority communities using their services, compared to the previous year. On an average week, there were now over 40 users from ethnic minorities (up from 8 in 1987) and 42 women using their services (up from 0.) London Friend also had disabled service users in mind, for example, an accessible toilet for those with physical disabilities was installed on the premises. The formulation of this Equal Opportunities Policy was both an acknowledgement and commitment from London Friend of the work they still had to do in ensuring their services offered support for all LGBTQ+ people.

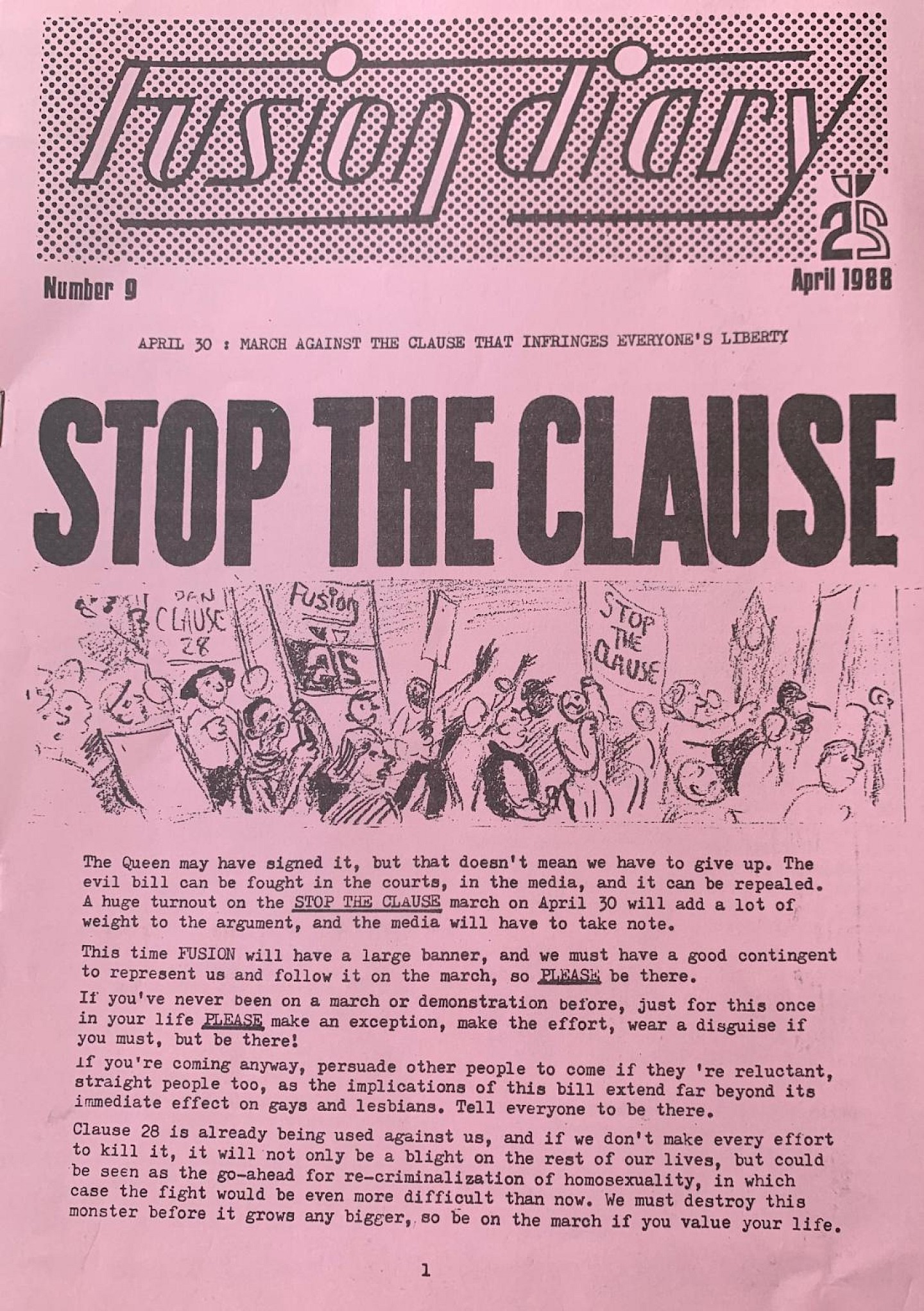

Stop the Clause

The Queen may have signed it, but that doesn't mean we have to give up. The evil bill can be fought in the courts, in the media, and it can be repealed. A huge turnout on the Stop The Clause march on Apffil 30th will add a lot of weight to the argument, and the media will have to take note.

This time Fusion will have a large banner, and we must have a good contingent to represent us and follow it on the march so please by there.

If you've never been on a march or demonstration before, just for this once in your life please make an exception, make the effort, wear a disguise if you must, but be there!

If you're coming anyway, persuade other people to come if they are relutant, straight people too, as the implications of this bill extend far beyong its immediate effect on gays and lesbians. Tell everyone to be there.

Clause 28 is already being used against us, and if we don't make every effort to kill it, it will not only be a blight on the rest of our lives, but could be seen as the go-ahead for the re-criminalization of homosexuality, in which case the fight could be even more difficult than now. We must destroy this monster before it grows any bigger, so be on the march if you value your life.

In the 1987 general election Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives won a third term in government, thanks partly to their manipulation of nostalgia for so-called family values. (In her speech to the Conservative Party Conference that year Thatcher attacked the idea that people had a right to be gay.) Buoyed by its success and by the wave of hysteria created by the HIV/AIDS crisis, the government passed the Local Government Act 1988, which forbid local authorities from ‘promot[ing] homosexuality or publish[ing] material with the intention of promoting homosexuality’. Local authorities were not to allow the teaching in their schools ‘of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.’

Although no successful prosecutions took place under Clause 28, as the relevant section of the 1988 Act came to be known, it ushered in a new era of homophobic bullying and persecution. But it also galvanised organised opposition, with campaigning groups, most notably Stonewall, being founded with the specific purpose of overturning the legislation. Although Tony Blair’s first Labour government failed to repeal the law in 2000 thanks to the efforts of the Conservative Baroness Young in the Lords, its repeal in England and Wales was eventually achieved in 2003. Many Conservative politicians, including David Cameron, Prime Minister from 2010 to 2016, would go on to voice deep regret for having supported the introduction or retention of the Clause.

Fusion, London Friend’s social and support group for men of colour, rallied all of its members to turn out in support of the ‘Stop the Clause March’ planned for 30 April 1988. In its newsletter for April 1988 Fusion encouraged readers who’d never demonstrated before in their lives to join the march. ‘Tell everyone to be there’, they urged, ‘straight people too.’ The fear that the Clause could open the way for the ‘recriminalisation of homosexuality’, as the newsletter put it, was not scaremongering.

It’s all too easy to forget that although anal sex between men had been decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967, the age of consent had been fixed at 21 for gay men, compared to 16 for heterosexuals. Discrimination remained in many other areas of everyday life. (Gay and bisexual men, and occasionally lesbians, continued to be arrested for public displays of affection.) Equality was still a long way off. The introduction of Clause 28 made it look as if things had started going backwards. Fusion wrote ‘We must destroy this monster before it grows any bigger, so be on the march if you value your life.’

Shakti, the South Asian Lesbian and Gay Network, held it’s first meeting at London Friend in 1988. It quickly grew from four members to over 200. Shakti provided a support network, which was especially important for people when they were coming out. They also provided a social network at their regular meetings at Friend and discos at the London Lesbian and Gay Centre.

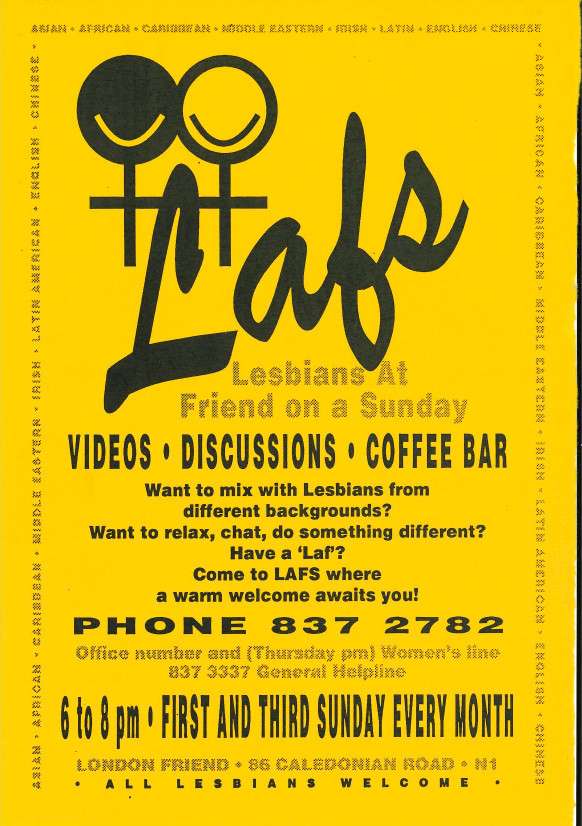

LAFS: Lesbians At Friend on a Sunday

Videos, Discussions, Coffee bar

Want to mix with lesbians from different backgrounds? Want to relax, chat, do something different? Have a 'Laf'? Come to LAFS where aa warm welcome awaits you!

The 1980s saw a dramatic increase in the numbers of women involved with London Friend. A women’s social group had been meeting on Thursday evenings for some years, but in December 1988 Friend launched a new support group, Lesbians at Friend on Sundays (LAFS), which met on the first and third Sunday evenings of each month. Earlier that year a group called Changes, for women coming to terms with being lesbian, had started to meet on the first, third and fifth Monday evenings, and in 1989 Onyx, a group for lesbians of colour, started holding meetings on the second and fourth Sundays.

LAFS was the idea of Olivette Cole-Wilson, a social work student at North London Polytechnic. While on a work placement at Friend, Olivette planned the group together with a team of volunteers and development workers. LAFS meetings were designed to provide relaxation and fun: there were discussions, quizzes and games. However, there were also visits by guest speakers, some of whom were known experts in their field, informative and thought-provoking videos were shown, and there was even the occasional live performance. Meetings finished with many members adjourning to a nearby pub.

London Friend has provided many support groups and services over the years, helping people with many serious and difficult issues, but it has also had fun, organising social events and gatherings, such as the Gay Pride march and christmas parties. In a London Friend newsletter dated 16th October 1989, London Friend is advertising its first ‘Friendly Disco’ at the London Lesbian and Gay Centre on 3rd November 1989, stating ‘it’ll have the same welcoming atmosphere as our groups.’ Events like these helped to build a community at London Friend.

Lesbians and Lafs

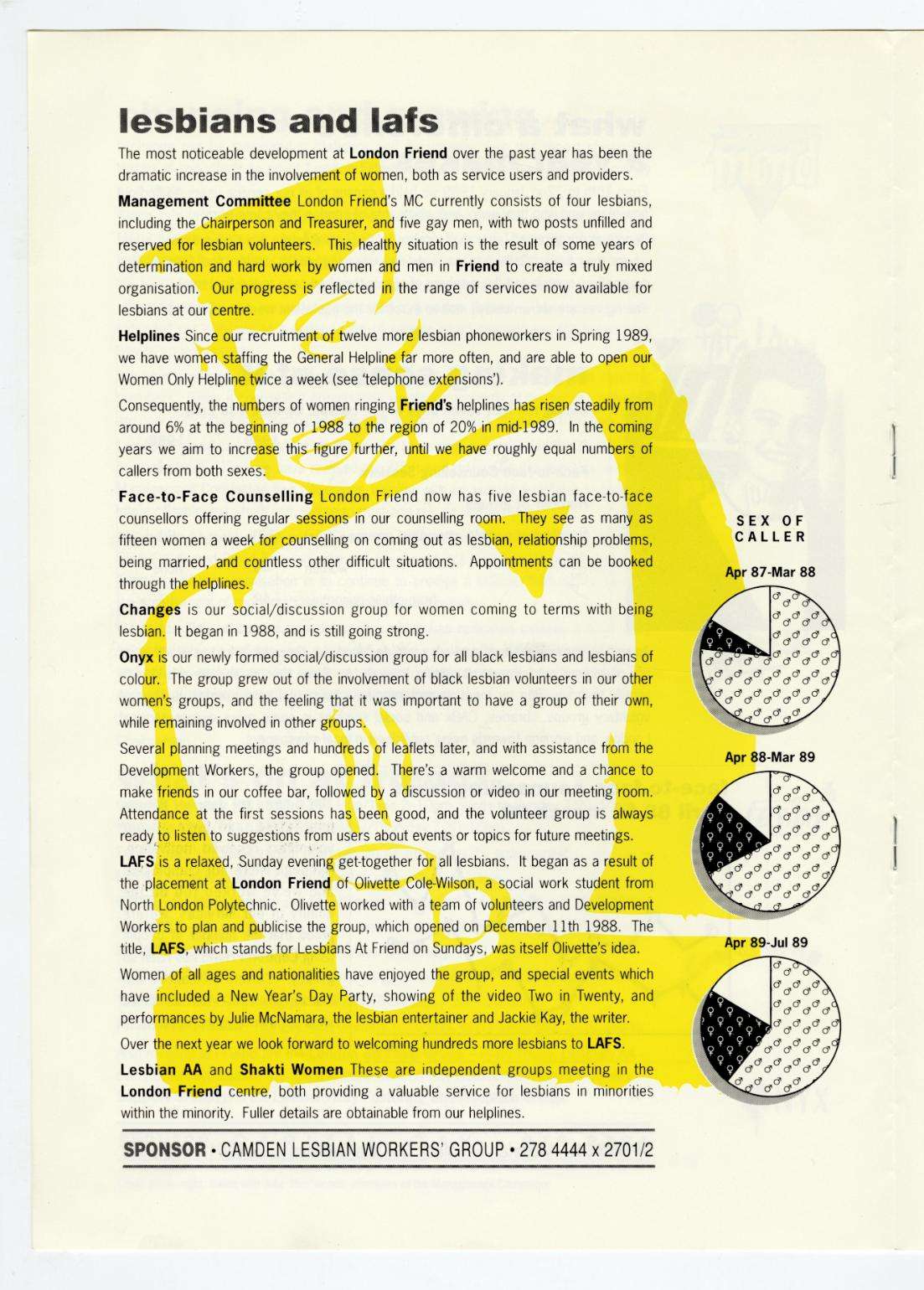

The most noticeable development at London Friend over the past year has been the dramatic increase in the involvement of women, both as service users and providers.

Management Committee: London Friend's MC currently consists of four lesbians including the Chairperson and Treasurer, and five gay men, with two posts unfilled and reserved for lesbian volunteers. This healthy situtation is the result of some years of determination and hard work by women and men in Friend to create a truly mixed organisation. Our progress is reflected in the range of services now available for lesbians at our centre.

Helplines: Since our recruitment of twelve more lesbian phoneworkers in Spring 1989, we have women staffing the General Helpline far more often, and are able to open our Women Only Helpline twice a week.

Consequently, the numbers of women ringing Friend's helplines has risen steadily from around 6 percent at the beginning of 1988 to the region og 20 percent in mid 1989. In the coming years we aim to increase this figure further, until we have roughly equal numbers of callers from both sexes.

Face-to-Face Counselling: London Friend now has five lesbian face-to-face counsellors offering regular sessions in our counselling room. They see as many as fifteen women a week for counselling on coming out as lesbian, relationship problems, being married and countless other difficult situations. Appointments can be booked through the helplines.

Changes is our social/discussion group for women coming to terms with being lesbian. It began in 1988 and is still going strong.

Onyx is our newly formed social/discussion group for all black lesbians and lesbians of colour. The group grew out of the involvement of black lesbian volunteers in our other women's groups, and the feeling that it was important to have a group of their own, while remaining involved in other groups.

Several planning meetings and hundreds of leaflets later, and with assistance from the Development Workers, the group opened. There's a warm welcome and a chance to make friends in our coffee bar, followed by a discussion or video in our meeting room. Attendance at the first sessions has been good, and the volunteer group is always ready to listen to suggestions from users about events or topics for future meetings.

LAFS is a relaxed, Sunday evening get-together for all lesbians. It began as a result of the placement at London Friend of Olivette Cole-Wilson, a social work student from North London Polytechnic. Olivette worked with a team of volunteers and Development Workers to plan and publicise the group, which opened on December 11th 1988. The title, LAFS, which stands for Lesbians At Friend on Sundays, was itself Olivette's idea.

Women of all ages and nationalities have enjoyed the group, and special events which have included a New Year's Day Party, showing of the video Two in Twenty, and performances by Julie McNamara, the lesbian entertainer and Jackie Kay, the writer. Over the next year we look forward to welcoming hundreds more lesbians to LAFS.

Lesbian AA and Shakti Women These are independent groups meeting in the London Friend centre, both providing a valuable service for lesbians in minorities within the minority. Fuller details are obtainable from our helplines.

Onyx, a group for lesbians of colour, was launched in October 1989. Onyx grew from the involvement of black lesbian volunteers in other groups including Lesbians at Friend on Sundays (LAFS). They felt it was important to have their own group while still staying involved in the other groups. The idea was that Onyx would exist alongside LAFS rather than be an alternative to it and many women were members of both groups. LAFS met on the first and third Sundays of the month, while Onyx met on the second and fourth Sundays of the month.

However, Onyx’s stay at London Friend was shortlived, and they left for the Camden Lesbian Centre in 1990. A few years later a race equality report on London Friend by Savi Hensman wrote about the group’s departure: ‘while some white service users and volunteers had been supportive, others had shown less respect and sensitivity … the damage to LF’s reputation among black lesbians at the time was considerable, and a residue of mistrust remains.’ The Race Equality Report, commissioned by London Friend, was part of London Friend’s work towards becoming a more diverse and inclusive organisation.

During the 1970s the Charity Commission refused to allow voluntary gay groups such as London Friend and London Gay Switchboard to register as charities, on the grounds that homosexuality was contrary to the public good. (None of the groups whose applications were turned down were in a strong enough financial position to challenge the Commissioners’ ruling.) Astonishingly, the Commissioners did award charitable status to a number of organisations working to eradicate homosexuality—the notorious Festival of Light, for example, which was founded in 1971 to oppose the so-called permissive society.

By 1982 the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, which Friend had once been part of, had had enough. In the February of that year it decided to set up its own charitable company to test the waters. It was not awarded charitable status. But after overhauling its constitution in order to be in a good position to make an application, National Friend became a registered charity in 1986. This huge source of encouragement was badly needed at a time when Friend was forced to quit its premises in Upper Street owing to rent increases. A few years later, in December 1989, London Friend became a registered charity.

Since its inception in 1972 London Friend had worked to increase the numbers of women using its services, working for them as counsellors and getting involved as volunteers. For example, 1988 saw the addition of Lesbians at London Friend and Changes, a group for women coming to terms with being lesbian. London Friend also wanted to recruit more women to serve on its management committee.

1990 was the first year that there was an equal number of men and women on London Friend’s management committee (six of each). This was a crucial milestone for London Friend as it moved towards providing a more equal mix of lesbian and gay support services.

In 1990 the Gay Men’s Choir (now London Gay Men’s Chorus) was co-founded by London Friend volunteers John Yates-Harold and Louis Loizou. They rehearsed in the basement of London Friend, and performed their first concert at London Friend at Christmas 1990, singing a programme of Christmas carols. However, they quickly outgrew London Friend and were forced to move to larger rehearsal spaces and performance venues.

In 1992 John wrote a mass, Undying Heart: A Requiem for AIDS, specifically for the choir. This was performed at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 30 October 1993, with performers including Peter Tatchell, Jimmi Harkishin, Gordon Warnecke and Georgina Hale reading poetry John had set to music in between the movements of the mass. The week before the choir had sung ‘Go West’ with the Pet Shop Boys at the London Palladium to raise money for new charity Stonewall.

How could London Friend become better at meeting the needs of black and minority ethnic lesbians and gay men?

Come along to 86 CALEDONIAN ROAD, LONDON N1 on SATURDAY 2 OCTOBER 1993 11AM-1PM with your views and experiences - all lesbians and gay men welcome.

Or contact Savi at the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre, Arch 196 Bellenden Road, London SE15 4RF or on 071-732-3885.

On its 21st birthday, London Friend highlighted improving racial equality within the organisation as a priority. In early 1993, it hired an external consultant, Savi Hensman, to produce a report about race equality in the organisation. The report was given to London Friend in December 1993.

Hensman’s report contained an assessment of the organisation’s current commitment to racial inclusivity. He had consulted volunteers, service users, and lesbian and gay members of the public following an advertising campaign which made use of flyers, posters, and items in newspapers. His report concluded that London Friend’s efforts to be more inclusive were largely working, but also set out some proposals for improvement. It suggested, for instance, that it could organise occasional brief courses on race equality and diversify its library.

In January 1999 London Friend was in danger of closing owing to a ‘cash crisis’. However, it had already begun a fundraising campaign and, although further efforts were needed, its newsletter for this period firmly suggests that it felt that it was well on its way to meeting its target of £6000 by the end of March: close to £4000 had been raised by the January, with £500 coming from a Pink Singers’ concert. Not included in the £4000 figure was the approximately £140 per week generated by the coffee bar and donations from groups and individuals who used London Friend’s premises. This regular income helped immensely.

IT'S OUR 30TH BIRTHDAY!

Give us a PRESENT at the Taxman's expense!

Help us reach our target of £30,000

With your help we can do it!

This will help us:

- Improve our telephone helpline service

- recruit extra Counsellors

- recruit more Support & Social Group facilitators

- improve our building and amenities

Help us to continue our work with:

- a one-off donation.

- a regular monthly or annual donation via Standing Order.

In 2002, London Friend was 30 years old. Here we can see a fundraising poster produced as part of its 30th birthday celebrations. To celebrate the milestone, London Friend resolved to raise £30,000. The poster explains how the money raised would enable Friend to upgrade the helpline service, recruit extra counsellors and social/support group facilitators, and make improvements to the building and amenities. Not only have London Friend’s milestone birthdays been times to reflect and celebrate, they have also provided a crucial opportunity to raise funds and generate publicity.

On 12 September 2006, London Friend launched Amistad, a new workshop for men of African descent and other men of colour.

A poster advertising Amistad prior to its launch explained that the workshop would provide a confidential and non-judgemental space for men of African descent and other men of colour to explore issues relating to their identity, culture and race as ‘gay men, men who love men, and men who have sex with men’.

The workshop was designed with a view to building up a group identity amongst participants and generating a mutually supportive environment within which group members would feel safe to open up and explore their feelings. Not only does this reflect the careful thought that goes into planning an appropriate structure for each social/support group and service, it also demonstrates how London Friend has responded to the need for new groups and services over the years.

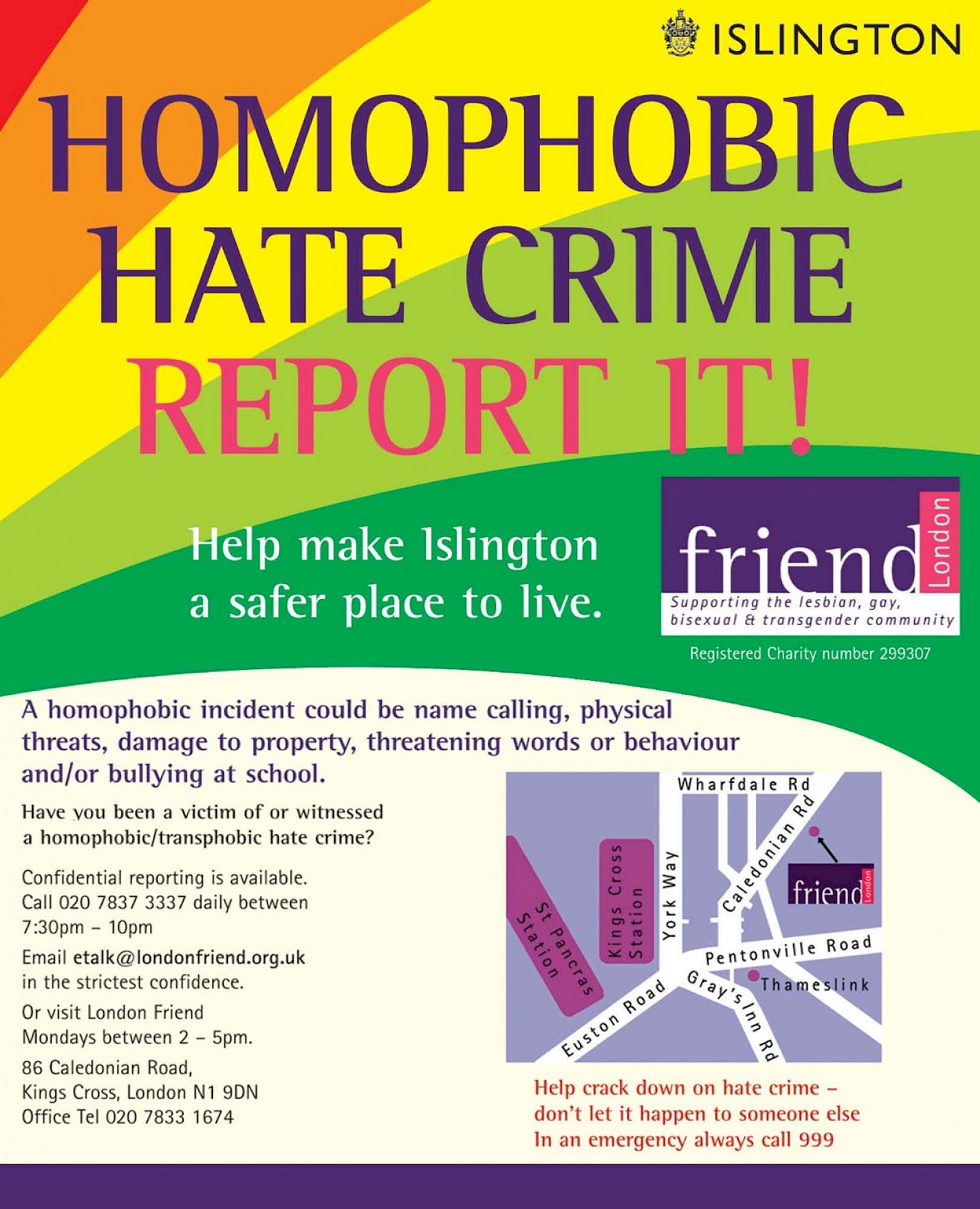

Throughout London Friend’s history we have supported LGBTQ+ people who have experienced discrimination, prejudice and crime directed at them because of hatred of LGBTQ+ people. In 2007 we received a small pot of funding to improve reporting of hate crime, offering a third-party route where people felt less confident to report to the Police directly.

Later, in 2015, London Friend joined the National LGBT Hate Crime Partnership, a group of 31 LGBTQ+ organisations jointly funded by the Equality and Human Rights Commission. The organisations worked together over 15 months to share knowledge and resources and build capacity across our sector to recognise and report hate crime, and support those affected by it.

Today London Friend partners with Galop, the LGBTQ+ anti-abuse charity, where we refer clients for assistance to report LGBTQ+ hate crime.

The 2000s marked a time of survival for London Friend. Core services continued to be provided, including the long-standing coming out groups and counselling. Some new services were added, including E-talk, one of the first digital LGBTQ+ services. For several years the organisation sustained operation thanks to a series of moderate legacies, supplemented by small grants.

Board Minutes from 2007 document the discussion about the charity’s future. A multi-year Business Plan proposed a new staffing structure and the appointment of a new Chief Executive role to focus on fundraising and expanding the organisation’s services.

Soon a new CEO, Matthew Halliday, was appointed, along with a full-time Volunteer Coordinator, Rita McLoughlin, and new funding starting coming in.

By the end of the decade London Friend had been identified as a potential new home for the Antidote LGBTQ+ drug and alcohol project and fundraising began in earnest. In 2010 the National Lottery Community Fund agreed to support Antidote for 4 years starting the following April. A new era for London Friend had begun.

In 2010 London Friend became a founder member of the National LGBT Partnership. The Partnership is a collection of LGBTQ+ organisations across England and collectively a member of the Department of Health’s Voluntary Sector Strategic Partners Programme (now the Health and Wellbeing Alliance). The Programme works with health charities and consortia as a way of engaging across a diverse set of health issues and communities.

The National LGBT Partnership provides strategic advice and information to policy-makers about health issues and inequalities affecting LGBTQ+ people. It works with the Department and the newly created bodies NHS England and Public Health England.

The National LGBT Partnership publishes a wide range of information and guidance, including ‘companion pieces’ to the Government’s Public Health and Social Care Outcomes Frameworks. These are developed to assist staff responsible for the planning, commissioning, and monitoring of health and social care services to address LGBTQ+ health inequalities.

London Friend has contributed to the development of many of these resources and leads on guidance around alcohol screening and brief interventions for LGBTQ+ people which is co-published with Public Health England.

In 2011 London Friend was able to buy the freehold to its building at 86 Caledonian Road, where it had been based since 1988. This was achieved with the help of an extensive fundraising campaign. 40 years since Friend began, it could look to the future knowing its base was secure.

In 2011 London Friend secured £500,000 of Lottery funding and, as a result, was able to combine with Antidote, the UK’s only LGBTQ+ run drug and alcohol support service. Antidote was set up independently in 2002 to deliver non-judgemental and free advice from trained LGBTQ+ staff and volunteers. Unique in its offering of a drug and alcohol service run by LGBTQ+ people for LGBTQ+ people, Antidote has been able to attract those who may have felt uncomfortable using NHS-run services and to support them if they needed help accessing the right services.

Antidote provided, and continues to provide, services ranging from one-to-one counselling, an advice helpline, weekly drop-in discussion sessions, and referrals to detox clinics and prescribing centres. Antidote also generates valuable healthcare research. For example, David Stuart (Education, Training and Outreach Manager for Antidote at the time) published research on sexualised drug use in the 2013 HIV Nursing journal. Antidote also does important work in training and educating healthcare professionals on issues affecting LGBTQ+ people. In the same year that London Friend took on Antidote, it also became a strategic advisor to the Department of Health. The merging of London Friend with Antidote marked a broadening of the services London Friend could provide and strengthened its connections with external healthcare services and providers.

Antidote’s move to London Friend brought new opportunities for partnership working, particular in addressing chemsex (the use of certain drugs by gay and bisexual men to enhance and prolong sexual activity). Antidote had been one of the first services in the UK to observe this emerging trend, with gay and bisexual men from all over London requesting support. The volume of clients coming to a single service and reporting using newer drugs like GHB/GBL and mephedrone meant that Antidote had been able to spot this trend long before chemsex was seen in mainstream drug treatment services.

Antidote responded by listening to its service users and understanding how chemsex was impacting them and amended its traditional drug treatment focus to include interventions that also jointly address sexual health and sexual behaviour change, and mental health and wellbeing. Crucially clients knew that the service understood what was going on for them and felt more comfortable about discussing their issues openly and honestly.

The National Lottery grant included resources for Antidote to work with other services—sexual health clinics and drug treatment services in particular—and during the four years of funding Antidote’s training and conference presentations reached 3,375 people from around 1,500 organisations. Sharing knowledge and experience was crucial in the response to people seeking support for chemsex, helping healthcare professionals to develop their existing skills and knowledge to provide a more inclusive service for a highly marginalised group of people.

Antidote also developed ground-breaking partnerships with NHS services that were themselves at the cutting-edge of the chemsex response. Club Drug Clinic is the UK’s first drug treatment service dedicated to drugs that were more likely to be used recreationally. The partnership offered Antidote clients access to a wider range of support (such as detoxification programmes) whilst in return, with 75% of the Clinic’s clients seeking support for chemsex, Antidote helped develop staff LGBTQ+ and chemsex competence. Antidote also started Code Clinic in partnership with 56 Dean Street, Europe’s largest sexual health clinic. Code was the first clinic in a sexual health setting specifically aimed at men involved in chemsex.

Today Antidote still leads its field as the largest drug and alcohol support service run by and for LGBTQ+ people. Clients have the opportunity to access one-to-one and group support with tailored programmes which address the early stages of making changes through to sustaining chemsex goals in the long term. Services like SWAP (the Structure Weekend Antidote Programme, an intensive 8-day therapeutic programme) and Sunday Sessions (with workshops on the underlying issues clients commonly report) are innovative groupwork programmes, the first of their kind anywhere in the world.

London Friend’s early support of the London TV/TS group from the 1970s demonstrates how much trans people were always part of the communities it supported. London Friend had also provided a long-standing meeting space for external groups like The Beaumont Society but did not run any services themselves. Developing better trans inclusion was a key goal for London Friend’s new Head of Service, Monty Moncrieff, who had joined the organisation in 2011, becoming CEO in 2012.

In 2012 London Friend was one of several organisations engaged in early discussions with cliniQ, a sexual health service for trans and non-binary people. cliniQ aimed to reduce the barriers trans and non-binary people can experience accessing sexual health support. Trans and non-binary people need sexual health support that is appropriate to their bodies, including in instances where they have undergone gender reassignment surgeries, but fear of ignorance or even prejudice from staff often deters them from seeking help.

cliniQ launched in 2012 as a holistic health and wellbeing service. In addition to the sexual health screening and advice trans people could get from the host sexual health service, clients could access additional support, with London Friend providing access to counselling and help with alcohol or other drug issues.

Later that year London Friend launched T on Tuesday, a support and social group for trans and non-binary people. By 2022 T on Tuesday is the busiest London Friend group.

Thanks to a chance meeting at Pride, London Friend began a partnership with Say It Loud Club, a group supporting LGBTQ+ refugees and asylum seekers. Say It Loud Club began to hold regular meetings and run workshops from the London Friend building. Using the building helped Say It Loud Club’s members feel more comfortable accessing other services at London Friend and some members began to work as volunteers.

As the partnership thrived, in 2017 London Friend secured funding for one year to further support the group, employing group coordinator Aloysius Ssali, increasing the number of group meetings, and providing free counselling for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers and refugees.

Group membership swelled, and it was clear Say It Loud Club had outgrown London Friend’s space. At the end of the year’s funding Say It Loud Club had increased its profile enormously and secured its own funding to sustain its future in a larger new home.

In 2014 London Friend published ‘Out Of Your Mind’, a report plus guidance for drug and alcohol services to develop their work with LGBTQ+ people funded through the Department of Health.

The guidance provided a simple self-assessment tool for drug and alcohol treatment services, for commissioners of services, and for frontline staff to audit their existing practice and identify areas requiring development. It also included recommendations for each group as well as for national policy. Many of these were subsequently adopted.

London Friend has also contributed to research and reports, including the 2014 Chemsex Study and Still Out There: An Exploration of LGBT Londoners’ Unmet Needs, published jointly in 2016 with other LGBTQ+ organisations and Trust For London. In 2020 London Friend published an engagement report based on work to identify the needs of lesbian, bisexual and trans women.

In 2016 London Friend was announced as a recipient of the Queen’s Award for Voluntary Service. The Award is the highest honour for voluntary groups in the UK and recognises outstanding contributions by volunteers. It is regarded as the equivalent of the MBE for voluntary groups.

The Queen’s Award took its place beside the National Diversity Award won by London Friend in 2014 and the GSK IMPACT Award won in 2016.

Antidote Manager Toni Hogg was recognised with an Attitude Pride Award in 2015, and appeared on the Independent on Sunday’s Rainbow List of the most influential LGBT people in the UK alongside London Friend’s CEO Monty Moncrieff.

In 2019 our Health and Wellbeing Coach Max Hadermann won a nOSCAR, the awards presented by NAZ for work within diverse communities. Max was recognised for his work with Latin communities through our SASH Partnership.

In 2018 London Friend CEO Monty Moncrieff was awarded an MBE for services to LGBT Equality.

In 2016 London Friend joined the London LGBT Domestic Abuse Partnership (DAP). The DAP is funded by London Councils and is the only specialist LGBT multi-agency Domestic Violence service. It is a way for LGBTQ+ people who have experienced domestic abuse to get the maximum amount of help with a minimum amount of hassle. The DAP is open to any LGBTQ+ person experiencing domestic violence who is living or working in London.

London Friend joined the DAP after the LGBT mental health charity Pace closed suddenly owing to funding difficulties. London Friend has provided counselling and run workshops for LGBTQ+ people who have experienced domestic abuse.

In 2017 London Friend worked with pop singer Olly Alexander on his BBC documentary Growing Up Gay. Olly examined the impact of being an LGBQ+ person growing up in a heteronormative and cisnormative society and the impact of homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia on LGBTQ+ people’s mental health.

Olly spoke with one of London Friend’s service users, following his journey and experiences.

In 2022 London Friend celebrated its 50th birthday with a year of heritage activities. London Friend is the oldest LGBTQ+ charity in the UK. It has supported the health and wellbeing of the LGBTQ+ community throughout this time, mostly through the efforts of its volunteers, supported by its dedicated team of staff. London Friend is needed as much now as ever and looks forward to continuing for another 50 years.